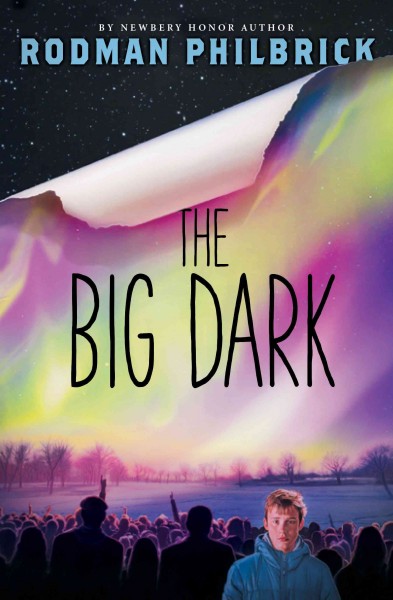

Living on the Northern Tier of Montana called the Hi-Line, I’ve seen the aurora borealis break dance with a rhythm similar to that described by Rodman Philbrick in his book The Big Dark: “Imagine a lightning bolt hitting a box of crayons and turning it into a colored steam. Like that. Electric colors rippling and pulsing as if they were alive” (3).

Living on the Northern Tier of Montana called the Hi-Line, I’ve seen the aurora borealis break dance with a rhythm similar to that described by Rodman Philbrick in his book The Big Dark: “Imagine a lightning bolt hitting a box of crayons and turning it into a colored steam. Like that. Electric colors rippling and pulsing as if they were alive” (3).

In The Big Dark, Philbrick, an award-winning author of the classic Freak the Mighty and numerous other books for young adults, not only writes in richly descriptive prose but posits a possible answer to the question: How would human kind respond to a massive solar flare or geomagnetic event that took out the power-grid, plunging the world into darkness and rendering all electronics, battery operations, and generators powerless? Presenting possible scenarios, Philbrick’s historical fiction account recalls the Carrington Event, a solar superstorm of 1859.

Middle schoolers Charlie Cobb and his best friend Gary Small, also known as Gronk, live in Harmony, New Hampshire. They join the entire town on New Year’s Eve to watch “the shape-shifting” lights in the sky. As all are mesmerized on a night that is so cold “you could sneeze icicles” (1), suddenly the lights go out, motors stop, and flashlights cease to function. When the generators all die, Charlie’s mom tells her children to stay busy as a cure to worry and that people must depend on the generosity of their neighbors. The school janitor and Harmony’s volunteer policeman, Reggie Kingman agrees, proclaiming that, more than firewood and food, the townspeople need hope.

When Harmony’s bully, Webster Bragg, starts preaching strange, hateful ideas, the town begins to divide. Bragg, the type of man who depends on chaos and fear, claims to base his ideas on his ability to think and reason when he tells the town’s population that democracy—which was “weak and deserved to die—[was] flicked off like a switch” (47). With the power grid destroyed and the plug pulled on civilization, Bragg believes that “nothing will ever be the same again” (47). Bragg and his family, who live in a compound and pack AR-15 assault rifles, threaten the town and convince many of the townspeople that his imperious form of power trumps the “Happy Talk” of “Mr. King Man.” Through Bragg, Philbrick weaves multiple, metaphoric meanings for the book’s title: ignorance, evil, and shadiness.

When—as a result of Bragg’s indirect actions—Mrs. Cobb experiences complications related to her diabetic condition, Charlie decides to attempt to reach a neighboring town on cross country skis and snowshoes in order to secure medication for his mother. Gronk tells Charlie, “It’s a pretty cool thing you’re doing” (90), and Charlie agrees that his audacious act might be cool if he accomplishes his mission. Charlie, who braves the coyotes, the elements that threaten to defeat him, and multiple other surprises in his attempt to secure the medication for his mother, decides he really hates the word if.

In what becomes a parallel to Balto’s Great Race of Mercy, Philbrick explores humankind’s behavior in desperate circumstances. With allusions to several Robert Frost poems, readers accompany Charlie on his quest, with “miles to go before he [sleeps]” and as the world is threatened to succumb to fire or ice.

- Posted by Donna