Not only unaware of the meaning of the word decorum but also oblivious as to how to show it, Angelo Fabrizzi detests the formal education his mother, Julietta, wishes upon him in Paris. Uninspired in the classroom, Angelo feels most alive when he’s working in his father’s workshop where he doodles car designs and fires up the welding torch to work and rework metal scraps into fantastical creations. Like his Italian father, Luca Fabrizzi, Angelo is a passionate and creative car-lover with a sweet tooth, who believes that magical ideas take shape under the influence of sugar.

After the front wheel drive sensation of 1934, Luca and his design partner, Christian Silvestre, have lost their inspiration, and a winning formula for another astonishing car has eluded them. Unless these two designers who “create works of engineering genius for beautiful people” (68) present a winning idea, the Money Men may pull their funding.

Angelo believes that “one thing alone [can] save [his] father’s career, rescue the company, and stop [his] parents splitting up” (6); they have to win the Paris Motor Show again. Like a World Cup for car designers, the Paris Motor Show plays host to many world debuts for concept vehicles, production models, and glimpses of the automotive future.

Angelo envisions their styling breakthrough in a flopped savory cheese pastry, a lopsided giant gougère with an almost aerodynamic form. Taking their inspiration from Angelo’s design, the two engineers build a prototype for the Paris Motor Show, which doesn’t go quite as planned. Angelo accepts responsibility for crushing his father’s career and vows to do everything in his power to make up for it.

Because of an impending German invasion, these two famous car designers and a thirteen-year-old boy escape to the remote countryside village of Regnac, France, to design and assemble a string of prototypes in a makeshift workshop. Owing the secrecy of their work to the war threat and the possibility of German spies, they work to create a car for the working class, a “people’s car” that will traverse a rutted road without spilling wine or breaking eggs.

In Regnac, the locals are mostly hostile to city folk, so the team experiences various gestures of inhospitality. For example, Angelo’s overtures at friendship with Camille are snubbed, and Phillipe looks at him with undiluted hatred.

When Angelo presents the first design, a Frankenstein Monster assembled from a pile of rusty metal work and old cogs, his father rejects it, but Paris factory owner Bertrand Hipaux captures the optimism of an inventor and encourages Angelo when he quips, “Some things aren’t meant to be. The rest aren’t meant to be yet” (89).

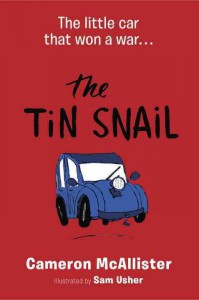

With The Tin Snail by Cameron McAllister, readers experience a unique historical fiction account of the French Resistance. Told from the perspective of car enthusiasts and commoners, the story puts a personal face on the events leading to World War II and their impact on French citizens. Those in Regnac turn out to be a fearsome group of heroes who take immense risks to sabotage the German war effort. McAllister creatively pens into his debut novel various colorful characters, includes an epilogue, and adds some back matter to reveal additional historical tidbits. Through his trials and setbacks, Angelo comes to accept that “people aren’t like cars. You can’t always fix something that’s broken (266).

- Posted by Donna