At the end of her sophomore year, Summer Everett will travel to France to visit her father, a famous but somewhat flaky artist. She will be spending her sixteenth birthday away from all that is familiar in Hudsonville, New York, where her mom is a philosophy professor. In Provence, she anticipates a summer of possibility, inundated with wild surprises, maybe even her first kiss. But without the abundant confidence and curvy figure of her BFF, Ruby Singh, Summer is plagued with uncertainty. In fact, Summer’s favorite question is what if: What if I answer my cell phone before I board the plane for France? Or what if I don’t?

At the end of her sophomore year, Summer Everett will travel to France to visit her father, a famous but somewhat flaky artist. She will be spending her sixteenth birthday away from all that is familiar in Hudsonville, New York, where her mom is a philosophy professor. In Provence, she anticipates a summer of possibility, inundated with wild surprises, maybe even her first kiss. But without the abundant confidence and curvy figure of her BFF, Ruby Singh, Summer is plagued with uncertainty. In fact, Summer’s favorite question is what if: What if I answer my cell phone before I board the plane for France? Or what if I don’t?

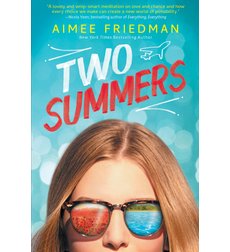

If an action has more than one possible outcome, then—if physicist Hugh Everett’s Many-Worlds theory is correct—the universe splits when that action is taken. This holds true even when a person chooses not to take an action. Borrowing from these theories of quantum physics, author Aimee Friedman splits Summer’s universe into two distinct universes to accommodate two possible outcomes. Readers of Two Summers ride along in these parallel universes to discover many complicated truths about family, friendship, and love.

In one universe, Summer risks losing her BFF, the girl with whom she has bonded by life’s difficulties and navigated Divorced Kid Land. As the two girls pursue different interests and experiment with change, they begin to drift apart. Summer takes a photography class and is partnered with her “Terrifying Crush” Hugh Tyson, the shy and somewhat nerdy son of the mayor that Summer has known since elementary school. Wren D’Amico also takes the class, and Summer comes to see a side to her that was previously unknown because “flagrantly, aggressively weird” (98) Wren has been pigeon-holed by bully and social climber Skye Oliveira. To Summer and Ruby, Skye has been Enemy Number One ever since she arrived in Hudsonville, “all super-long hair, sports prowess, and snide comments” (83). Now, the girl that Ruby once called “the essence of evil distilled in human form” (82) is worthy of her friendship and attention.

In the other, Summer—who is nervous around boys—meets the sexy waiter Jacques Cassel, encounters the mysterious Eloise, a bully not unlike Skye—all popularity and privilege—and longs for her absent father. In this world of poppies, croissants, and cobblestones, Summer also transforms from passive passenger, no longer watching life go by, to a more spontaneous, take charge person.

In both, readers get a separate but similar view of Summer’s stormy, fractured, and secret-drenched life. We experience Summer’s sense of loss mingled with freedom, the same sensations that accompany divorce, break-ups, and truth-telling. And we see Summer come alive as she discovers truths about her identity.

Although in some ways Two Summers by Aimee Friedman can be called a family, friendship, and romance novel, it is also a book about science—blending philosophy, psychology, quantum physics, and cosmology. Friedman adds an art angle as well, offering something for every reader! Not only with allusions to literature and to famous painters/paintings but also with the photography thread, Friedman explores art’s power to give us new perspective. She describes the eye as a private lens and photography—a Greek derivation for drawing with light—as capable of sharpening the eye as we shift perspective to see something in a new light from another’s vantage point.

Similar to Libba Bray’s Going Bovine, the allusions in Friedman’s novel oscillate between the obvious and the subtle. Summer lives on Rip Van Winkle Road (perhaps she has been sleeping through life, unawares?), her cat’s name is Ro (after Schrödinger’s cat), her love interest is named Hugh (after physicist Hugh Everett?), and she has a predilection for the what if question (the Uncertainty Principle, perhaps?).

Although humans find discomfort in uncertainty, Friedman cleverly juxtaposes art and science to remind us that “uncertainty isn’t always a bad thing. If not for uncertainty, people would never let go of grudges or secrets or fears” (304). We also are reminded about the value of contradiction and of being two-faced: “Everyone has different faces that they show to different people. Everyone is a contradiction” (308). Ultimately, Friedman invites us to welcome the strange because, in the words of the dying Hamlet: “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, / Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

Like philosophy, adolescence is a search for understanding, a time when youth are seeking to make sense of the universe and their place in it. Yet so much about this tumultuous time defies reason and creates confusion; thus, a young adult can feel translocated, as if in another country where everything is puzzlingly different. Just as travel invites discovery and perspective-shifting, so does life itself.

- Posted by Donna