Resembling a collection of short stories with the clever and mischievous sixteen-year-old witch, Kendra

Resembling a collection of short stories with the clever and mischievous sixteen-year-old witch, Kendra

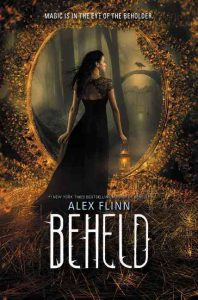

Hilferty as a unifying character, Beheld by Alex Flinn does some serious genre-blending and blurring. Part fairy tale, part historical fiction, part romance, and part mystery, Beheld—with its heroes, struggles, and allegories—reveals insight into what it means to be human while conveying its layered theme and multiple morals.

The main plot thread features Kendra’s search for James Brandon, her beloved soulmate. Four other stories run parallel to Kendra’s in that the characters also seek transformation through human relationships. Ann Putnam’s story, which brought back memories of reading The Crucible by Arthur Miller, begins the book. With references to talking wolves, wearing red capes, and being wary of wolves, Finn clearly alludes to Little Red Riding Hood. Like all children, Ann wishes to be cared about and cared for, to be appreciated, and to be thought good and worthy of notice or attention. But her desires—especially her fantasies about warm, magic, exotic places like Barbados—have grave consequences.

Other human truths also occur in Ann’s story—how fear interferes with rationale thought and how society often conditions us to think—two truths that remind readers of the importance of thinking for ourselves and allowing conscience and common sense to guide our decisions, rather than succumbing to the bandwagon effect or to insidious performances of peer pressure. This tale also invites discussion on an important question—To what degree does our fear of women with power contribute to our fear of witches? Early in the book, Kendra posits: “To be a woman, and to express strong opinions, causes one to be called a witch. There will always be those who fear women with power, even if the power is merely in our tongues” (46-47).

The basic human desires to be loved and to be wanted emerges again in Beheld’s second story about Cornelia and Karl. With its relationship angle, this story alludes to Rumpelstiltskin and how we are often seduced by beauty or enchanted by a magical voice, one that tells us what we wish to hear. It further discusses how we often trap ourselves with our own doubts. We may think that men have power over women, that limited means are commensurate with power so that the wealthy have more choices, or that we have no choice, when in reality we may not have fully explored our options or we may be afraid to reach out to others, asking for their help.

This fractured fairy tale shares additional human truths—namely that good and kind people can abandon us and that “sometimes people have to do things they do not wish to do, in order to be rewarded” (126) or in order to effect a desired change. This tale also reminds us that we all have talents that make us special, although we don’t ourselves always realize their value or how fortunate it is sometimes, not to get what we want. This truth reminded me of the paradox in the ancient Chinese curse: “May your every wish be granted.” Another topic deserving of deeper thought occurs when Cornelia and Rumpelstiltskin discuss books and their reasons for reading. Rum claims that schadenfreude, the satisfaction or pleasure felt at someone else’s misfortune—a condition that may make us feel better about our own lives—is the best reason for reading. Later in the novel, the topic of reading again surfaces. This time the characters speculate about the power of books: “Books allow us to be what we will never be in reality, have what we will never have” (132). Readers can explore their own reasons for reading and what power they consider books to possess.

The final two stories of Grace and Phillip—an allusion to East of the Sun and West of the Moon—and Amanda Lasky and Christopher Burke, which alludes to The Ugly Duckling, are equally thought-provoking as they continue to explore Finn’s layered theme and multiple morals revolving around the desire to transform the world or ourselves so that we can live with contentment. Like all stories, Finn’s collection features shared experiences about searching for solutions to problematic issues in our lives. Because these final two focus more on the role appearances and physical beauty play in motivating human behavior, they move readers to contemplate how we might act if we ever encounter a related situation. They explore the mystery of searching for that special person who will love and accept us for who we are.

Similar to Patricia Wrede’s fantasy novel Thirteenth Child, Finn’s Beheld—with its serious examination of what it means to be human—strikes a kindred chord that transcends cultural differences and bonds us. Because they explore human issues that strike psychological and emotional chords, fairy tales will always appeal to us. We read fairy tales to discover what transformations need to occur in our world or in ourselves so that we can quiet the noise and dance happily. Finn seems to have discovered this truth, as many of her books are adaptations and retellings of these common experiences.

- Posted by Donna