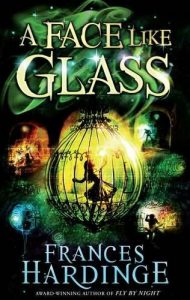

Imagine living underground without sunlight, sky, fresh air, or space to run unfettered. Set in an underground city called Caverna, A Face Like Glass by Frances Hardinge imagines that possibility for the reader. An amazing machine where nothing happens naturally or without planning, the city is home to many craftsmen and women who create the world’s delicacies: wines, cheeses, spices, perfumes, and balms. Despite these elegant refinements with their magical properties, Caverna is a dark and drab and dank place, where even the citizenry have been deprived of real emotion. Instead, they select a suitable Face from the 200 they have been taught in infancy. Much like the social hierarchy in other science fiction tales, Caverna has its aristocracy, “a glittering Court, teetering always on the tightrope of the Grand Steward’s whims” (8); its artisans, its servants, and its drudges. If they wish for a new expression, the affluent elite can hire a Facesmith, an individual specializing in face-designs.

Imagine living underground without sunlight, sky, fresh air, or space to run unfettered. Set in an underground city called Caverna, A Face Like Glass by Frances Hardinge imagines that possibility for the reader. An amazing machine where nothing happens naturally or without planning, the city is home to many craftsmen and women who create the world’s delicacies: wines, cheeses, spices, perfumes, and balms. Despite these elegant refinements with their magical properties, Caverna is a dark and drab and dank place, where even the citizenry have been deprived of real emotion. Instead, they select a suitable Face from the 200 they have been taught in infancy. Much like the social hierarchy in other science fiction tales, Caverna has its aristocracy, “a glittering Court, teetering always on the tightrope of the Grand Steward’s whims” (8); its artisans, its servants, and its drudges. If they wish for a new expression, the affluent elite can hire a Facesmith, an individual specializing in face-designs.

At age six or seven, a girl tumbles into this subterranean world. She is rescued from a vat of curdling Neverfell milk by Cheesemaster Moormoth Grandible, a rebel in Caverna, it turns out. Memory of her past and parentage are lost to Neverfell, the name Grandible bestows upon her—given her origin. Aware of her value, Grandible doesn’t permit Neverfell to navigate beyond his private tunnels, an impregnable dairy castle where he makes cheeses that can induce visions or even explode. Nor does Grandible allow Neverfell to meet anyone else without wearing a mask. Not understanding the mask’s purpose and never having seen her reflection, Neverfell thinks she must be hideous. In fact, she is unable to conceal her inner thoughts, which are mirrored in her expressions, making Neverfell an anomaly in Caverna, where stock emotions prevail and lies are an art.

As she concocts the story of her previous life, Neverfell relies on her imagination and on the fragments that she assembles from stories, rumors, and overheard conversations to replace what she considers a stolen memory and a lost history. However, the most compelling aspect of this gothic fairytale may be Neverfell’s insatiable curiosity and unpredictability. Like a child with freshly unwrapped gifts, Neverfell loves new memories and thoughts to turn over. She also has a talent for tinkering and taking things apart, inventing tools to simplify the cheese making process, and “learning the pleasure of seeing cog obey cog” (8), almost like magic. She is a “tangle of fidget and frisk, with feet that [will] not stay still” (7).

Grandible knows that the less Neverfell knows, the longer she will live, but Neverfell’s curiosity is her nemesis. As Neverfell attempts to track down her secret past, she becomes the target for thieves, assassins, and a variety of other dangers, including ignorance, talking to strangers, and failing to remember table etiquette. With every discovery, come confusion and mistakes, so that Neverfell is often “thumping mismatched jigsaw pieces together to make them fit” (205). It is the Kleptomancer who finally sheds some light on Neverfell’s mysterious situation: “Find something that is important, something on which you suspect many plans rely, and remove it. . . . The people who want to use you and the people who want you dead will be in a race to find you before the other does” (244).

Even though as a pawn Neverfell finds potential allies–like Erstwhile, Zouelle, Madame Appeline, and Maxim Childersin–which of these are true supporters and which are just masters in the arts of intrigue and manipulation? Neverfell’s inexperience with disloyalty and her naivete, in general, make her an easy target for emotional blackmail since she wishes to protect and to trust those she considers friends.

In addition to its rich detail and convoluted plot, A Face Like Glass offers an interesting definition of wine: “Popular among the rich and bored, . . . [wine] can clear out useless or ugly memories” (63). The novel also makes a reader wish to know more about the cheese maker’s craft or to be a connoisseur of cheeses so valuable that they’re like gold in a vault, and it invites occasional pauses to ponder:

- Can a person invent a face without feeling the emotion the expression is meant to communicate?

- Is there a difference between being happy and believing you’re happy?

- How true is Maxim Childersin’s statement, “It [is] easier to create mayhem than to impose order” (472)?

- The author calls Neverfell’s desire to protect her friends one of her “greatest weaknesses.” Consider features that make loyalty a weakness and others that render it a strength.

Readers will likely discover additional reasons for reading Hardinge’s book, which joins the ranks of other great sci-fi and fantasy writers like Aldous Huxley, Philip Pullman, Neil Gaiman, and Madeleine L’Engle who explore important issues surrounding the nature of friendship and loyalty, the value of intellectual excitement and discovery, the significance of courage, and the danger of excessive luxury, ambition, or power.

- Posted by Donna