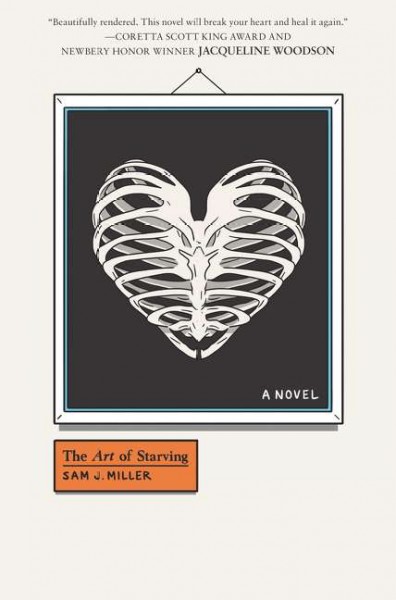

Sometimes a story can take us to a place of understanding and awareness. Cultural identity literature at its best, The Art of Starving by Sam J. Miller transports readers to a place so familiar we wonder whether we haven’t been here before, where we know the people and can relate to their challenges, where we share their hunger for fulfillment, their starvation for affection, attention, and validation, and their hunger for justice.

Sometimes a story can take us to a place of understanding and awareness. Cultural identity literature at its best, The Art of Starving by Sam J. Miller transports readers to a place so familiar we wonder whether we haven’t been here before, where we know the people and can relate to their challenges, where we share their hunger for fulfillment, their starvation for affection, attention, and validation, and their hunger for justice.

This book will appeal to readers who enjoyed Someday This Pain Will Be Useful to You by Peter Cameron or Wintergirls by Laurie Halse Anderson. Although it is a book for all readers, it is especially one for teens struggling with body image or identity issues—those who feel lost, lonely, and isolated, those with suicidal ideation who need to know they’re not alone, that they need to reach out and ask for help.

The story’s protagonist, sixteen-year-old Matt who has been identified by therapists as an at-risk youth with suicidal ideation, believes he is a source of shame and embarrassment, that he is an “enormous fat greasy disgusting creature” (12). Matt fixates on what makes him different—his flaming red hair, his sexual preference, his poverty, his absent father, and his alcoholic mother—mostly unaware that these differences which make him miserable might also make him a stronger, improved version of humanity.

Searching for control and wanting some share of the power in the pecking order at Hudson High in New York, Matt controls his eating habits by counting calories and establishing rules. Under the influence of food deprivation, Matt discovers powers of concentration and focus. Led by his hunger, his senses on high alert, Matt sees, hears, and smells things others cannot. For example, he trains himself to disentangle the threads of detail present in smells, which carry a plethora of information in diverse pieces, and he believes he can tune out all distractions and focus on what his senses tell him, on what his hunger is helping him to smell, see, hear, and feel. Once he makes this discovery, Matt feels invincible and doesn’t want to lose his Peter Parker powers. Like an aphrodisiac which makes him feel invincible, this power fuels the vicious cycle of Matt’s eating disorder. Although Matt knows that starving himself is bad, it feels so good. When he’s ultra-aware, Matt can confront “Hudson High’s soccer stars; the shrewd-eyed roosters at the top of [the high school] pecking order” (5): Ott, Bastien, and Tariq, revelers in athletic stardom, parties, and privilege. Self-harm gives Matt power to set right a world gone rotten and to bring the scales of justice back into balance. Only after many negative experiences and considerable time does Matt realize that when he focuses on what he wants to see and learn and smell and feel, he can miss reality.

Through his characters Ott, Bastien, and Tariq, Miller defines bullying styles: “Big and dumb and broad-shouldered” (15), Ott embodies the physical style of abuse. A slim-hipped, smiling psychopath, Bastien excels at emotional abuse; his brutality is all verbal, as he strings together snatches of hate speech. Tariq plays the by-stander role, a watcher who witnesses—without intervention—what his friends say and do. “He is their audience. The one they perform for” (16), essentially validating them with laughter or silent approval.

An intelligent, handsome, Syrian young man, Tariq Murat is also the target of Matt’s lust interests, but Matt believes Tariq somehow lured his sister Maya into harm’s way, so Matt lusts and hates Tariq in equal measure. With his sister missing, Matt has lost his lifeline, the person who has kept him tethered in the chaos of his life. In her absence, Matt gives freer rein to his self-harm practices as he focuses on his Mission of Bloody Revenge, giving him a sense of purpose. As he asserts his power to solve the missing person mystery, to prove he’s not weak, that he’s stronger than his emotions, “strong enough to bend and break his body into obedience” (260), strong enough to control his own destiny, Matt almost destroys himself with his own twisted, starving mind.

More than a boy with an eating disorder, more than a gay person, and more than a person who wonders whether “having no dad or having an asshole dad” (147) fucks a person up more, Matt emerges from his abyss damaged but strong enough to realize that when bad things happen, it doesn’t help to place blame or to wish for alternate outcomes. In his newly discovered strength, he not only realizes that he cannot bend the fabric of space and time and reality to get what he wants but also learns to accept that when bad things happen, he can choose whether to allow them to cause hurt. From him, readers gain knowledge about deriving emotional fulfillment from more than physical desire or physical appearance or physical pleasure. We also learn the connection between physical appearance and happiness; that in our desperation for guidance, “rulebooks are bullshit;” that our “bodies are clumsy machines full of strange parts that need expensive maintenance—and we do things to them that have consequences we can’t anticipate” (333); that “life is a miserable shit-show for lots of very good people” (343); and that people only have the power over us that we give them, a lesson which reminded me of Eleanor Roosevelt’s famous quote, “No one can make you feel inferior without your consent.” Matt ultimately realizes that power deriving from anger, hate, fear, and shame leads to destruction; instead, “the greatest power comes from love, from knowing who you are and standing proudly in it” (365).

Despite its heart-rending moments that plunge a reader to the depths of despair, Miller’s debut novel also rides some waves of familiar experience with descriptions like the high school cafeteria, where amid “the stink of scorched taco ‘meat’ and spilled sour milk; hundreds of hormonal mammals heap abuse on each other and preen for potential mates” (23). He also invites us to ask the important philosophical question: How do you fill your hole? We all occasionally experience feelings of emptiness, and how we choose to fill that hole has immense importance for emotional, physical, and mental health. We can’t look outside ourselves to find approval. From Maya and her punk music, readers see the value in channeling addictive or obsessive traits into creating rather than in destroying.

- Posted by Donna