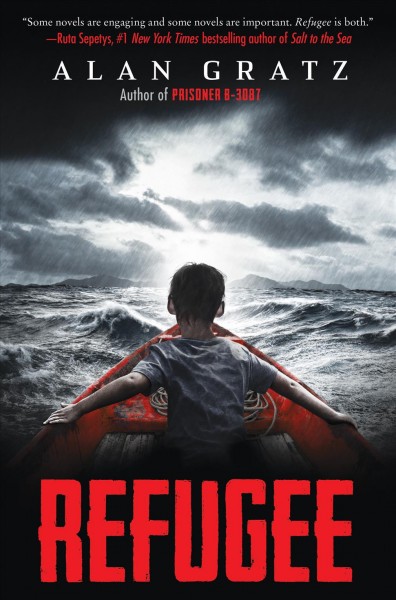

Three stories told, three countries represented, and three lives profiled. Despite the years that separate them, the trinity of humanity featured in Alan Gratz’s novel Refugee experience remarkable and horrifying similarities with intersecting conclusions.

Three stories told, three countries represented, and three lives profiled. Despite the years that separate them, the trinity of humanity featured in Alan Gratz’s novel Refugee experience remarkable and horrifying similarities with intersecting conclusions.

Imagine feeling unwanted, dirty, and illegal. Imagine hearing sirens, soldiers, shouting, gunfire, breaking glass, and screams daily. Imagine thinking that if you want to live, you have to leave your homeland and all that is familiar. These are the realities of three refugees and their families: Josef Landau, a barely thirteen Jewish boy living in Germany in 1939 under the reign of Adolph Hitler; Isabel Fernandez, a pre-teen Cuban citizen enduring the fickle, power-hungry policies of Fidel Castro in 1994; and Mahmoud Bishara, a twelve-year old boy in Aleppo, Syria, ruled by President Assad in 2015.

With Refugee, Gratz puts a human face on the tragic reality of war, how it makes one twitchy, paranoid, and afraid; how it fills the heart with longing, terror, and loss; and how nothing is more important than family loyalty, desire for freedom, and a sense of humor and hope.

Another of Gratz’s key points is how some things are invisible until they happen to us, that we may be blind to ignorance and hate as diseases until we are victims or until a story opens our eyes. This story has potential to open our eyes and our hearts. As I read, I found myself not only wishing for a promising tomorrow but nodding with sad agreement at Mahmoud’s realization: “They only see us when we do something they don’t want us to do” (214), “when we do something they don’t like” (302). When refugees stay where they are supposed to, whether that be in the ruins of Aleppo or behind the fences of a refugee camp, people can forget about them. But when refugees try to cross the border into another country or sleep on a shop’s front stoop or jump in front of a car or pray on the decks of ferries, people can’t ignore them any longer. Although being invisible in Syria kept Mahmoud alive, he begins to wonder if being invisible in Europe might be the death of him and his family. He eventually determines the real truth: “Whether you were visible or invisible, it was all about how other people reacted to you. . . . If you were invisible, the bad people couldn’t hurt you, that was true. But the good people couldn’t help you, either” (281).

Isabel, too, learns this truth. If you want to escape starvation and civil rights abuses, you have to make noise, take action, and make yourself heard. Because she realizes it is better to stand up and to stand out than to silently sit on the sidelines hoping things will get better, she trades her trumpet—her most valuable possession—for gasoline to escape Cuba, hoping to get her life back. To her, nothing is more important than keeping her family together and making it to Florida.

Sharing that commitment to family and hoping to escape the persecution and the murder of Jews in Germany, Josef takes risks and makes sacrifices to take back what was taken from him and his family: the Jewish rituals, customs, and cultural practices; the Torah, Hebrew prayers, and synagogue worship.

Although the characters are fictional, their tales are based on true stories. In the back matter of his book, Gratz includes facts about refugees, as well as route maps of paths travelled. Readers follow the three families on their journeys with three movements: escaping the horror that drives them from their homes, trying to survive ocean crossings and border patrols and criminals looking to profit, and then starting over in a new country to rebuild lives among citizens who often don’t speak the same language or practice the same religion or honor professional degrees.

With this eye-opening and heart-breaking book, Gratz humanizes the struggle of immigrants seeking survival, making it an important book for upper elementary students to learn about both historical and contemporary social issues.

- Posted by Donna