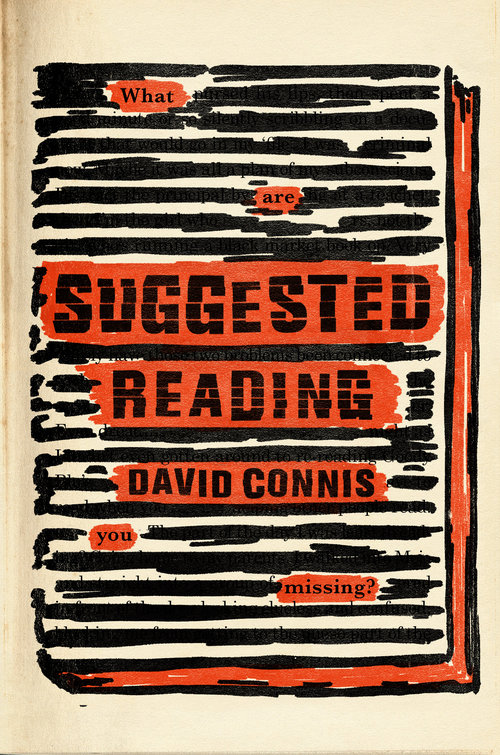

As a confirmed bibliophile who believes in the power of books, I didn’t need Suggested Reading by Dave Connis to convince me that a person can be undone by a book or that books serve like eyeglasses, giving us new insight by providing a perspective we didn’t realize we were missing.

As a confirmed bibliophile who believes in the power of books, I didn’t need Suggested Reading by Dave Connis to convince me that a person can be undone by a book or that books serve like eyeglasses, giving us new insight by providing a perspective we didn’t realize we were missing.

Similarly, Connis’ protagonist, Clara Evans has been built by books; they have shaped, changed, inspired, and guided her to her senior year at Lupton Academy (LA), a private school in Tennessee. On the first day of her last year in high school, Clara learns about a school policy about “prohibited media”: LA’s librarian Mr. Caywell has been ordered to pull all the banned books from the library. Shocked by this sinister attempt at censorship, Clara challenges Mr. Caywell’s willingness to comply, and he responds: “If I made a huge to-do about it, I’d lose my job. I’d rather be here to point students in alternative directions . . . than not be here at all. Sometimes the game has to be played by someone else’s rules. And sometimes those rules don’t benefit the players. The thing is, if you don’t play the game at all, you can’t help others win” (29).

Fueled by anger, Clara is determined to fight this policy that suggests that books about rape, young people being bullied because they’re gay, the intricacies of the human condition, or racism are somehow painfully relevant but inappropriate topics for young adults. Clara is also offended that the school administration believes they can make decisions about books and write them off as dirty, wrong, or unwholesome.

With her foundation rocked by this new policy, Clara seeks out the help of her best friend LiQuiana Carson, the student body president, to set right this world gone rotten. And like Jerry Renault in Robert Cormier’s The Chocolate War, they do “dare [to] disturb the universe.” But how far will they carry their beliefs and principles?

Even though Clara may jeopardize her status as a finalist for the Founder’s Scholarship—her ticket to a post-secondary education at Vanderbilt—she refuses to accept the censorship situation. Instead, she exercises her right to protest by starting an underground library, the UnLib. Not a sneaky person by nature or one to disrupt the status quo, she’s now pushing good literature out of her locker—an underworld of banned books.

When her disruption turns out to have unintended consequences, Clara begins to question her motives: Did she act on her beliefs and principles or out of revenge? Is she power-tripping or trying to prove that books are valuable? Can a giver of a book be guilty by simply being the giver? Or is she just a dictator in the opposite: using books as weapons and telling people what to read rather than what not to read?

With all of these questions swirling in her brain, Clara grows confused about the line between anger and hate and about whether believing in something means having to make the ultimate sacrifice. On the enlightenment journey, the reader not only experiences Clara’s frustration but learns the consequences of pushing the boundaries and that there is a difference between standing against and standing for something. Hate can be the worst place to start if you want to change something, according to Clara’s mother: “You stand up because you believe, not because you want to win” (246).

In the process of untangling her confusion and defining her life philosophy, Clara learns the value of looking instead of assuming, the harm in pigeon-holing people, and the universal presence of hurt. She also learns that books, like people, are wild things that can’t’ be tamed. And that stories have the power to start wars as well as to end them and that “unrestricted access to books allows us to be challenged and changed, to learn new things and to critically think about those things and not be afraid of them, to be better than we were before we read them” (336).

Connis’ book is a powerful one—not only as a testament to a book’s ability to shift fault lines in our lives but as an inciting force to start “fires that show the grandness of the world [and] the depth of others” (382). He invites us all to call upon our bravery, strength, hope, and hurt to advocate for one another and to make a positive impact. He also reminds us that we bring our whole selves to the pages of a book—“Every single darkness. Every single light. Every single passion. Every single hurt” (355). These layers that comprise us act like filters when we read, catching certain particles and letting others pass based on our idiosyncratic experiences. Given this diversity of experience, it can never be up to a book to make sure people don’t kill themselves or hate someone. We use our minds and make choices. Books might ignite a spark, inspiring action that changes lives, or they might provide a light that melts ignorance and hate, showing us a new path to take. Because “books illuminate something different for all of us” (382), their power is unpredictable.

- Posted by Donna