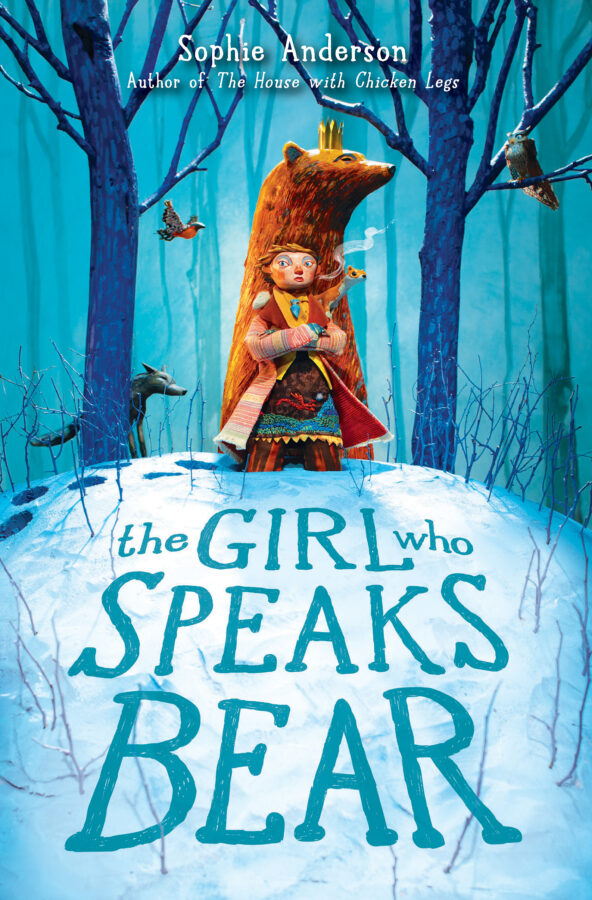

Growing up, we all face conflicts about our identities. For those who are unsure of their pasts and parentage, those conflicts escalate. Sophie Anderson explores this truth in her fantasy tale for young readers, The Girl Who Speaks Bear.

Growing up, we all face conflicts about our identities. For those who are unsure of their pasts and parentage, those conflicts escalate. Sophie Anderson explores this truth in her fantasy tale for young readers, The Girl Who Speaks Bear.

As the plot unfolds, twelve-year-old Yanka feels alienated by her unusual size and strength, unsure whether to attribute those changes to a growth spurt or to some anomaly. In the village, she is often reminded of her differences, despite the efforts of her best friend Sasha to include her and to remind her that she is strong and brave and kind. Because she hears the call of the bullfinches and can detect the forest’s moods, Yanka is pulled to the Snow Forest. Further pulling her are Anatoly’s stories which are fantastical but hold some truth—stories about Princess Nastasya and Smey the Fire Dragon.

Yanka also feels the pull of her strong and unstoppable mother-figure. A healer and herbalist with the wisdom of the Snow Forest inside her, Mamochka encountered Yanka one day while picking herbs for her medicines. Thinking the baby had been abandoned, Mamochka takes Yanka home with her, raising and nurturing her as her own daughter.

Now, several years later, Yanka is convinced that the story of her past and where she’s from resides in the forest. When she inexplicably develops the legs of a bear, Yanka–embarrassed and ashamed–runs away into the woods to find answers. But what will her discovery mean for her future, and what dangers will she encounter?

While Yanka wishes to be carried into the future so she can discover all the stories and secrets of her past, she faces the battle between a wish and a curse. From Yanka, readers learn that sometimes we are so busy looking to the future that we look past the gifts of the present and what we already have. Other lessons come in realizing there are many definitions of family and that memories make us who we are. As Yanka finds a sense of belonging, she determines that what really matters is how we see ourselves. Our perspective and our attitude will determine whether something is a gift or a curse.

Furthermore, Yanka recognizes that strength is more than muscles, fangs, claws, and facing things alone. It’s having a plan and a herd to help. It means accepting that we have more control over what we become than we realize.

In navigating these truths, Yanka finds her inner hero and is able to combat the destructive forces of greed, selfishness, and cruelty. On her hero’s journey, Yanka comes to understand that sometimes we have to lose or leave behind what we had before to realize how much we cherish it.

Anderson’s animal characters are also well-developed, especially Yanka’s pet weasel, Mousetrap. From him, Yanka gleans considerable wisdom, not the least of which is this tidbit: “Somebody’s external appearance doesn’t change what’s inside” (256). And when readers recall Mousetrap’s war dance, they will likely smile with the memory of his antics.

Another perk of Anderson’s novel is its seamless presentation of Russian villagers. Readers will learn about the customs (i.e. Winter Festival, kalyuka flutes, sledging) and foods (i.e. golubtsy, sbiten, pryaniki, knish, sushki) of the villagers.

- Posted by Donna