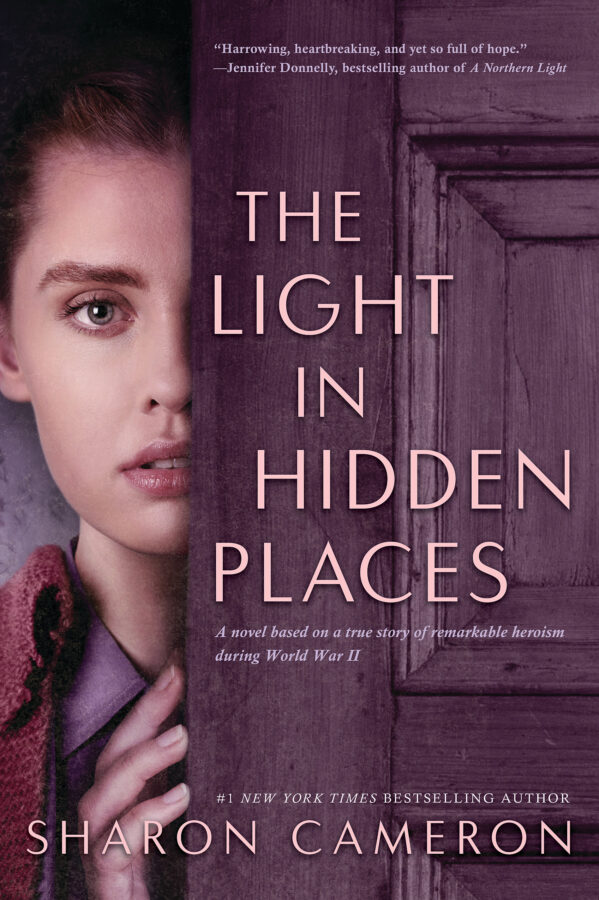

The Light in Hidden Places by Sharon Cameron joins the ranks of a long line of stories like Number the Stars by Lois Lowry (1998), My Brother’s Secret by Dan Smith (2015), Anna and the Swallow Man by Gavriel Savit (2016), and Don’t Tell the Nazis by Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch (2017). Such novels capture the youth experience during the era of World War II. Cameron’s, though, is based on the true story of the remarkable heroism of the Podgórska sisters, Stefani and Helena, two Polish Catholics who defied the law and safe-guarded several Jews. Of her brave but risky behavior, Stefani asks, “Who else is there, . . . if not me? (241) and vows to save these precious lives for as long as she can.

The Light in Hidden Places by Sharon Cameron joins the ranks of a long line of stories like Number the Stars by Lois Lowry (1998), My Brother’s Secret by Dan Smith (2015), Anna and the Swallow Man by Gavriel Savit (2016), and Don’t Tell the Nazis by Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch (2017). Such novels capture the youth experience during the era of World War II. Cameron’s, though, is based on the true story of the remarkable heroism of the Podgórska sisters, Stefani and Helena, two Polish Catholics who defied the law and safe-guarded several Jews. Of her brave but risky behavior, Stefani asks, “Who else is there, . . . if not me? (241) and vows to save these precious lives for as long as she can.

The story opens in 1942 after the Russian invasion of Przemyśl, Poland, but reverts to 1939 to trace the ugly acts of wartime, including how fear and sadness often give way to cruelty. Where before it had been easy to imagine terrible things as some kind of mistake, Stefi comes to realize that “the misguided ideas of a misguided leader” (52) can transform people. She confronts the depth of hatred and the horrors of war—times during which a child can be beaten to death in the street simply for being Jewish and when soldiers revel in the joy of hatred, happy to cause another person death and pain.

Every part of Stefani defies such evil. From her own experiences with a hot-headed temper, she knows that fear and anger get a person nowhere, but experiencing the many faces of evil—from the murdering labor camp of Belzec to the smaller killing machines created by ghettos where starvation and disease like typhus were common—inspires a deep anger that transforms into civic action.

Besides documenting the conditions in Przemyśl before and after the Second World War, Cameron’s historical fiction account oscillates between extremes—the desire to live and the certainty of death. Readers can only imagine the discomfort of being alive when your family is dead or envision a world where death is a shadow at the edge of every light. Under the influence of guilt and fright, facing starvation and hardship, Stefi is even afraid of love because it will make her hurt. Out of necessity, she becomes an artful and expert liar. Even her six-year-old sister emerges as clever, resourceful, and courageous under extreme duress.

Despite such ghoulish circumstances, occasions of love and relief surface. Izio, Max, and Leah Diamant are illustrations of goodness and kindness. Despite the hardship, these individuals, as well as several others like Emilika, show compassion. Even when Emilika explains to Stefani that her suggestion to help the Jews is “a one in a million chance, and that means there are nine hundred and ninety-nine thousand other chances to die,” Stefi responds, “But it’s not zero” (157). The rest of us can only imagine what it is like to be that brave, that selfless, and that responsible.

Through Max, who becomes the leader of the Jewish hidden, the reader further learns what it means to be a survivor, even when a person has been caged and reduced to nothing: “When you watch little children being murdered while you hide in a hole in the ground, too afraid to come out, you know that you are nothing. When whole countries want you dead, when thousands cheer for speeches about your destruction, when the dogs of the guards are treated better than you are, then . . . you know you are nothing” (149).

Although we all live through days that we don’t ever want back, Cameron’s book documents a period when many lives were shattered and would never fit back together again. Cameron describes the dark tentacles of World War II that keep stretching deep into present day; the scars, hurt, and repercussions still ripple with loss. “Loss of family. Loss of friends. Loss of histories and futures. Fear that cannot be forgotten” (Authors Note).

- Posted by Donna