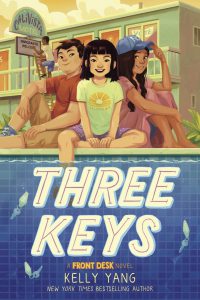

Try as I might, I was unable to limit my review of Three Keys by Kelly Yang to three keys to its greatness. I started with

Try as I might, I was unable to limit my review of Three Keys by Kelly Yang to three keys to its greatness. I started with

- It’s about a goat named Scape and the issue of immigration and how it’s easy to blame those in a weak spot;

- It proves that although most people don’t change, some people do; and

- It shares how small interactions have the power to change minds and to make a big impact for those vulnerable to exploitation, abuses, misinformation, and hopelessness.

But I realized I couldn’t stop with that short list. Yang’s book goes beyond any simple storyline to capture some deep themes about finding solutions to social problems. By working locally and thinking globally, Yang demonstrates how a group of sixth graders opens people’s eyes to the far-reaching effects of California’s Proposition 187, which sought to exclude undocumented children from California schools, making it illegal for them to get an education or use public services like hospitals. Yang’s protagonist Mia Tang works from behind her school desk and the front desk of her family’s Calivista Motel to effect positive change and to renounce hate and racism. In the process, she also proves that racism and bigotry aren’t only white afflictions and that we need laws which embody the vision and core values of the United States of America.

The deportation of undocumented immigrants becomes real when it touches the life of Mia’s friend Lupe Garcia, whose father is arrested and jailed as an illegal immigrant. To help her friend, Mia contacts Prisha Patel, an Indian attorney, who points out that “actions are illegal, not people” (187) and that since Lupe doesn’t have green ears and a finger that glows, she’s not an alien. Through Lupe’s experiences, readers further learn that being undocumented is “like being a pencil, when everyone else is a pen . . . You worry you can be erased [at] anytime” (57). That one piece of paper defines “the difference between living in freedom and living in fear” (171).

From Lupe, who wishes to be an artist, readers also gain insight into how families are like trees: “If we set our roots down deep enough, we can’t be moved” (170).

While Yang’s book follows this effort to free Lupe’s dad and to reunite the Garcia family, it also explores other threads and uncovers various lessons. For example, speaking with an accent doesn’t make a person a foreigner, nor should it be something one seeks to get rid of. Instead, an accent—according to Mia’s mother—is “your very own unique signature of all the places you’ve been. Like stamps in a passport. It has nothing to do with where you’re going” (36).

Furthermore, forgetting the Chinese breakfast food jiambing, abandoning chopsticks in favor of a fork, or preferring ice cream over red bean shaved ice that tastes like mashed potatoes to Mia doesn’t make an Americanized Chinese person a banana.

From the brave and caring Mia, readers can learn the greatest lesson of all: When you realize something is wrong, it is your social responsibility to say something. Readers will also read about the deep sacrifices that some parents make so that their children can have more opportunities, greater freedom, and a better education.

Another piece of Yang’s tapestry comes from Mia’s interactions with character Jason Yao, who reminds us that children are not always mirrors of their parents. Mia tells Jason that we have to follow our dreams—that nobody can take them away. Additionally, just because we don’t see someone of our race profiled in the papers doesn’t mean we can’t pursue the profession of our dreams. We can’t allow someone else’s doubts or beliefs to define us or to create fear; instead, we must control our fear so that it doesn’t control us because we’re stronger than we think. By focusing on our gifts, anything is possible.

Finally, Yang’s book imparts the three keys of friendship: “You gotta listen, you gotta care, and most importantly, you gotta keep trying” (245). It encourages readers not only to develop those keys but to find other values living inside us and just waiting to be discovered, values like the Chinese yi qi (loyalty) and like advocacy. Such advocacy will involve confronting issues of power and privilege that dominate current social practices, asking questions about our world, seeing beyond stereotypes, and welcoming alternate ways of knowing and being.

- Posted by Donna