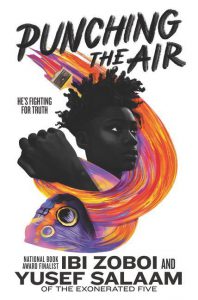

Ibi Zoboi and Yusef Salaam have teamed up to co-author Punching the Air, an important book about the cycle of racial injustice that continues to plague this country, especially in regards to the unfairness of our criminal justice system. Readers of Jason Reynolds, Walter Dean Myers, and Elizabeth Acevedo will likely be fans of this book.

Ibi Zoboi and Yusef Salaam have teamed up to co-author Punching the Air, an important book about the cycle of racial injustice that continues to plague this country, especially in regards to the unfairness of our criminal justice system. Readers of Jason Reynolds, Walter Dean Myers, and Elizabeth Acevedo will likely be fans of this book.

Punching the Air features Amal, a sixteen-year-old art student who dreams, writes poetry, draws, paints, and rides his skateboard. On a fateful night, he finds himself in the wrong place at the wrong time, choices and circumstances that completely upend his life. A fallen angel, Amal—whose name coincidentally means hope—has been cast into the hell of false accusations, trumped up evidence, and injustice.

A prisoner of blind justice, Amal feels like he’s punching the air as he attempts to share the truth about his role in what happened to Jeremy Mathis. When his efforts fall on deaf ears, he finds himself in a jail cell, a box. This box metaphor takes on an extended meaning under the artistry of Zoboi and Salaam.

Written as a novel in verse, Punching the Air also borrows from the concrete poetry genre to produce a visual representation accented by abstract and surreal illustrations. In addition, the book features powerful allusions to Maya Angelo’s poem “Still I Rise” and to other voices of color. Allusions to the world of art beyond poetry is also rich and extensive with some of the chapters taking on the names of famous artwork or styles: The Scream, Picasso Face, The Thinker, Black Mona Lisa, Guernica, and The Persistence of Memory.

As he seeks to find answers and to survive the hell that is prison, Amal asks: “What do you see when you see me?” (93). In coping with frustration over the futility of his efforts to overcome his dire predicament, Amal’s greatest tools are his mouth, his words, his rhymes, and his art. As he unravels, Amal discovers that he can put himself back together with words. He paints “in words and voices, rhymes and rhythm, and every whisper, every conversation beats a drum in [his] mind at full blast” (262).

In addition, Amal finds lifelines in Umi, his mother and number one supporter “whose love was not enough to keep [him] free” (235) but whose faith and persistence sustain him and give him hope; in Zenobia, a female friend from the outside who writes him letters; in Kadon, a fellow inmate and one of his Corners; in Dr. Kwesi Bennu, an ex-convict and inspirational speaker who reminds the young inmates of the power of story; and in Imani Dawson, a poet, educator, and activist who visits the prison to conduct poetry workshops and who calls herself a prison abolitionist. From her encouragement, Amal discovers his truth.

- Posted by Donna