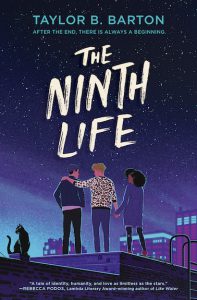

The Ninth Life by Taylor B. Barton is a book about hope, family, grief, friendship, romance, and identity. But most of all, it is a book about fighting for love—that raw, untamed, and messy emotion—and a book about the monstrosity of being human, which is both horrible and beautiful.

The Ninth Life by Taylor B. Barton is a book about hope, family, grief, friendship, romance, and identity. But most of all, it is a book about fighting for love—that raw, untamed, and messy emotion—and a book about the monstrosity of being human, which is both horrible and beautiful.

As Caesar’s feline life is coming to a close, a life bursting with endless amounts of love, he can’t imagine living without Ophelia Matherson and her dog Missy. His life as Ophelia’s cat was a full one; it had taught him kindness and brought him friendship. In that life, he loved a girl who loved him back, and that made death feel like an impossible bridge to cross; he didn’t want to go.

So, he makes a deal with the goddess Zosma to rejoin Ophelia for his ninth and final life. When he awakens from death in the body of seventeen-year-old Austin Price, who had died of cardiac arrest, who had been a recreational drug user, and who had loved Cooper Cott but remembers none of that and whether there was any commitment, he is unprepared for the messiness of human emotion and the price tag of his wish.

In his past lives as Phnom, the great tiger of Cambodia; Bilhana, a cocky snow leopard in Nepal; King, the vengeful circus lion; Monty, the alley cat; an unnamed clumsy kitten ripped from his mother and drowned; Aziza, the proud cheetah; Dior, the sphynx; and Caesar, a cat rescued from a cruel life to one of boundless love, “want had always been water, food, sustenance, and shelter. Want had always been home” (86), someplace comfortable, lived-in, and shared.

As a funny, handsome, and weird human adolescent, Austin is lost in uncertainty. Startled into wanting something that he shouldn’t want and left contemplating the lines of friendship and romance, Austin worries about overlapping heart strings and wonders how to avoid tangling them when feelings are invested.

Ophelia is the finest form of confusion. She’s smart, stubborn, assertive, and passionate about what she wants, and she aspires to attend Juilliard and to dance as a ballerina. When Austin thinks of Ophelia, he thinks of “stardust and faraway planets and the curve of her hips” (107). But when he looks at Cooper, he thinks of lightning storms and the darkest part of the ocean. Both make Austin’s heart happy, so he concludes that love is a vicious and mean thing—jumbled, confusing, complicated, and capable of hurt.

Barton aptly captures the complexity of human emotion with creative descriptions. At one point, she/they spends a page and a half describing the “raging, beautiful, impossible light” (170) that kissing produces, as well as the transformational power that such intimacy and touch engenders while knotted together and clinging to another being.

From the novel’s key characters: Ophelia, Austin, Cooper, and Ryan, readers also learn that friendship comes in different shapes and sizes and that the labels we assign to people have limitations since they cannot fully capture a person, place, or thing. For example, friendship can be romance-adjacent, a partnership, a companionship, or something else entirely. Ophelia resists Austin’s desire to categorize her, saying: “I’m not anything. I know I’m a girl and I know I’m not straight and that’s about it. Alignment and sexuality and gender are weird and I’m allergic to commitment, so for now, I’m Ophelia and that’s that” (141).

Commenting further on the topic of identity, Ophelia wisely utters: “Even if you don’t know what it means yet or how to define it or what to do with it, being exactly who you are is a brave thing, Austin” (142).

Austin. Ophelia, and Cooper also know grief. Having lost loved ones, they understand that grief can render a person powerless and confused. Ophelia’s therapist tells her that “grief makes people believe life will be better if everything went back to the way things were before they lost whoever it is they lost. Because if we accept what happened, if we let our lives change, things will be worse. The trick isn’t grief giving us a choice between wanting the impossible and moving on, it’s that no matter what, even if we let go, things will always be worse. Nothing will ever be the same” (201).

Because life has no rewind button, no reset switch that can be pressed to make things right, no undo button that can reset time after making a terrible mistake, Barton’s characters discover that all of their actions have consequences and that the things they say and do have a lasting impact. Under the influence of such understanding, they learn to reassemble their lives around the wounds.

- Posted by Donna