When Alder Madigan and Oak Carson first meet as next door neighbors in a Los Angeles, California, neighborhood, the two fifth graders decide they don’t like one another. Complicating any chance at a friendship is the mystery of their mothers’ dislike for one another.

When Alder Madigan and Oak Carson first meet as next door neighbors in a Los Angeles, California, neighborhood, the two fifth graders decide they don’t like one another. Complicating any chance at a friendship is the mystery of their mothers’ dislike for one another.

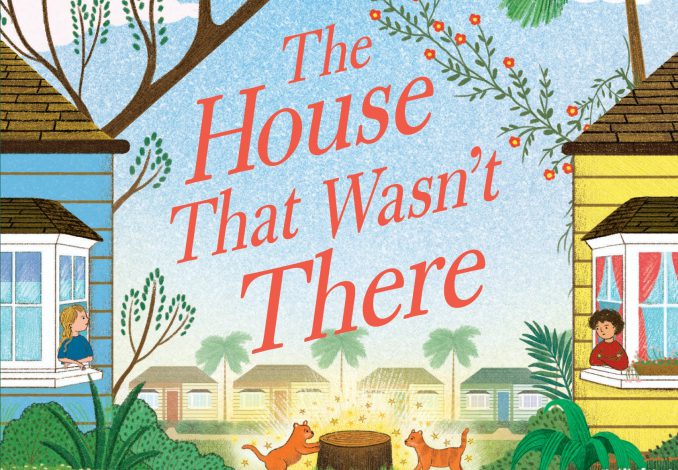

However, as time and coincidences transpire, the two accept that change is hard and that sometimes, one thing—like anger or a tree—has to end to make room for something else. Furthermore, the universe appears to have other plans. Those realizations—in the midst of a kitten coincidence, an apparition of a house that isn’t there inhabited by Mort the opossum, and the disappearance and reappearance of a book—all contribute to a weirdness that eventually the two tweens decide they need to team up to resolve.

Such is the plot of The House That Wasn’t There by Elana K. Arnold, a story that also embraces the topic of middle school friendship challenges and perceptions of belonging. Now that Alder’s best friend Marcus has found a kindred spirit in Beck—who is nice, funny, athletic, and popular—Alder wonders where he fits in and struggles to find his place. After all, Alder, whose folk musician dad died eight years ago, is not an athlete but a lover of words and a knitter of yarns—the sweater kind. He believes that his love for language and words likely came from his dad. “Writing music, after all, is about playing with words and the ways they fit together, with meaning and rhythm and rhyme” (154).

While Alder navigates his loneliness and what he sees as gender markers, Oak has her own unsettled feelings to sort through. Because she wasn’t consulted, Oak isn’t happy about the family move from San Francisco and has her anger to deal with. What feels reasonable to Oak and what her mother considers reasonable are often not the same, and dealing with hard choices that someone else got to make is equally difficult to understand when you’re eleven-years-old.

When the two tree kids—a term used by Faith the bus driver to refer to Alder and Oak—finally speak the words, “Let’s be friends,” they discover the magic in those words. Together they search out the secrets held by the universe. With the help of an interdisciplinary project developed by their teacher, Mr. Rivera, they learn that despite complications and misunderstandings, everything is connected: “language arts and math, kittens and portals, old friends and new friends, past and present.

Arnold also shares a metaphor about love’s being a house that we cannot see, “a third place between two people” (277). Once built, that house will always be there, even if we turn our back on it or walk away.

In addition to her handling tough topics with grace—including the difficulty of making friends, fractured friendships, a deceased parent, and enjoying non-gender norm hobbies—Arnold alludes to rich science topics, such as Schrödinger’s Cat, Nikola Tesla’s cat, and feline teleportation.

- Posted by Donna