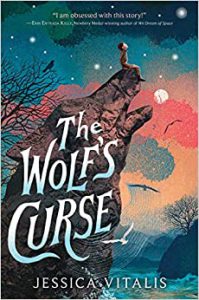

Although not the historical fiction giant that is The Book Thief by Markus Zusak, The Wolf’s Curse by Jessica Vitalis uses Death as one of its narrators. Through her twelve-year-old protagonist Gauge, the Carpenter’s grandson, Vitalis explores the social custom of rites of passage and life after death.

Although not the historical fiction giant that is The Book Thief by Markus Zusak, The Wolf’s Curse by Jessica Vitalis uses Death as one of its narrators. Through her twelve-year-old protagonist Gauge, the Carpenter’s grandson, Vitalis explores the social custom of rites of passage and life after death.

After his grandpapá dies, Gauge no longer has the protection he needs from Lord Mayor Vulpine who is terrorizing the village of Bouge and who blames Gauge for the death of his wife. To protect him from the Guards, who wish to arrest Gauge and set him out to sea to die because he is a Voyant capable of seeing The Great White Wolf, the Blacksmith and his daughter, Roux, take him in and risk imprisonment by giving him refuge. Living his life by the same principle, the Blacksmith tells his daughter: “Change is made in small increments, one right action at a time” (114). But soon, the Blacksmith, too, passes, leaving the two youth alone to wonder about the ritual of Release.

The culture in Bouge believe that the stars in the Sea-in-the-Sky are lanterns lit by their loved ones who have sailed on. Several merchants are profiting from the people’s grief—from the Vessel-maker and the Rope-weaver to the Steward who performs the last rites. Because the rituals are not always performed the same, Gauge begins to doubt their accuracy and questions their need. Risking his life, he follows the Wolf to unravel the mystery. Gauge and Roux learn too early that there is something about death that makes living difficult. Still, with her quick wit and fierce determination, Roux takes up Gauge’s cause and assists him in his fact-finding mission.

In the process of unravelling the mystery, the two learn other valuable lessons. When Gauge experiences moments of deep despair, he recalls his grandfather’s advice to follow his heart, saying: “It’s as true as any compass out there” (125).

Like his grandpapá, Gauge also believes that carving is an act of creation and of rejuvenation. “Gauge’s fingers itch to work, to channel his emotions into something productive. Grandpapá always said there was no finer pastime than carving. He taught Gauge to search for the beauty locked inside a piece of wood, to judge it based on what it might become” (164).

Roux never saw metal like her father did—”as something to be shaped and molded, like a puzzle” (233). But that is how Gauge feels about carpentry. “He loves everything about it—the smell of freshly cut wood, picturing something in his mind and then watching it take shape, the satisfaction that comes each time he puts the finishing touch on a piece of furniture” (233). Consequently, he concludes that passions must be like trees, coming in all different shapes and sizes.

With a focus on grief and anger, Vitalis also addresses the power of emotion. Through her characters, Vitalis encourages readers to see that we often are too busy seeking revenge or too busy proving we’re right to actually see the truth and to accept our responsibility. When anger or grief are clouding our judgment, we tend to seek a scapegoat, shifting the blame from ourselves. Or we use our anger as a shield, allowing it to cloak our grief. Until we face the truth of our loss, we cannot heal.

- Posted by Donna