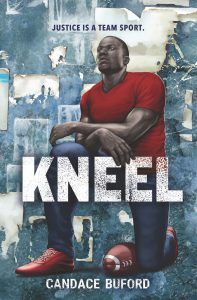

Readers of Kim Johnson and Angie Thomas will likely enjoy Kneel by Candace Buford. Set in Monroe, Louisiana, Kneel follows the story of the Jackson Jaguars high school football team and their two star players: Marion LaSalle and Russell Boudreaux. Football is the two athletes’ ticket out of Monroe and out of poverty.

Readers of Kim Johnson and Angie Thomas will likely enjoy Kneel by Candace Buford. Set in Monroe, Louisiana, Kneel follows the story of the Jackson Jaguars high school football team and their two star players: Marion LaSalle and Russell Boudreaux. Football is the two athletes’ ticket out of Monroe and out of poverty.

Marion is possibly the best quarterback in Louisiana, and Russell is a regionally ranked tight end. For both, their bodies are their greatest assets. Although Russell is no slouch in the classroom, the field is the only place where Marion is on top. However, that is taken from him when he is falsely accused and arrested for assault, battery, and resisting arrest.

In protest and in support of his friend and teammate, Russell takes a knee at the next game. His refusal to be silent about injustice has repercussions, however. These come not only from his coach and teammates but from the neighboring town and his own family. Football was his duty to the family, and now he may have failed in upholding that unwritten pact. He begins to question the merits of peaceful protest.

At school, Monroe’s English Teacher Ms. Jabbar invites her students to read texts like “i sing of Olaf” by e.e. cummings, “Still I Rise” by Maya Angelou, and If Beale Street Could Talk by James Baldwin. She believes that “art should rouse the senses. . . literature should pierce [the] soul. It should stick with you after you read it” (160).

Russell and another classmate, Gabby Dupre take inspiration from this literature to fight for justice. In the process, they realize that speaking truth to power is often difficult. Those who speak out are often villainized and lose their ability to live their passions.

Thrust together for a collaborative English project, Gabby and Russell begin to develop feelings for one another. Bonding over their belief that silence protects violence, the two want to speak out but also wish to fly under the radar. Their words become their source of power. They borrow from Baldwin: “Neither love nor terror makes one blind: indifference makes one blind” (77).

Still, Russell struggles; he wants to be outspoken, but he doesn’t want to lose his chances at a football scholarship. How can he walk that fine line to effect change and still not jeopardize his future? Ms. J tells him: “It’s okay to question your motives and to review your actions, Rus. You should do those things . . . But sometimes you have to trust your gut and not look back” (162).

Feeling boxed in by violence and injustice, Rus resists acceptance of the status quo. Believing that “a life unencumbered by prejudice is a life worth living, worth demanding, even worth fighting for” (196), Rus refuses to be silent.

With this novel that explores racial injustice, Buford gives readers hope that with our civic involvement and advocacy for change, we can build bridges of justice. It is also a reminder that “for evil to flourish, it only requires good men to do nothing,” words often attributed to Simon Wiesenthal.

- Posted by Donna