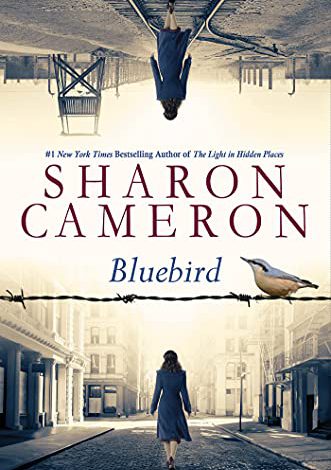

Not just another Holocaust survivor’s story, Bluebird by Sharon Cameron is both fascinating and horrifying. It prompts readers to consider along with Cameron’s protagonist: “Is this the world? Where nothing is fair? Where it is impossible not to cry? Where wars are not glorious or noble, just dirty and blood-soaked” (94)? It also prompts us to ask: Is it always better to know the past and the things that have happened? Cameron’s protagonist decides, “If you don’t know, then you can’t understand what justice is” (105).

Not just another Holocaust survivor’s story, Bluebird by Sharon Cameron is both fascinating and horrifying. It prompts readers to consider along with Cameron’s protagonist: “Is this the world? Where nothing is fair? Where it is impossible not to cry? Where wars are not glorious or noble, just dirty and blood-soaked” (94)? It also prompts us to ask: Is it always better to know the past and the things that have happened? Cameron’s protagonist decides, “If you don’t know, then you can’t understand what justice is” (105).

After experiencing the atrocities in Berlin during Hitler’s reign, Inge von Emmerich concludes that she has survived for a reason and devises a goal to achieve justice. That justice will involve confronting her father, reciting the names of 27 victims on whom he conducted mind experiments to “improve them,” and holding him accountable for his crimes against humanity.

A monster of a man, Inge’s papa was famous for saying: “Emotion should never enter into judgment. Emotion makes correct choices difficult, and that is weakness (12). . . . Coddling the weak with kindness only encourages their weakness (39). . . . All you really need to make another person do what you wish is the application of the right leverage. That is simple science. And a more elegant solution. I proved this time and time again at the camp, in experiment after experiment. . . . And the idea of the ultimate control . . . . It is so tempting” (346).

Because he sincerely believes in the noble pursuit of science and sees the Führer as a man of principle and vision, Doctor von Emmerich considers World War II “a glorious war,” an opportunity to use the prisoners in concentration camps like Sachsenhausen as lab rats (346). During this “golden age of science,” Hitler removed all barriers to scientific discovery. When Inge is forced to confront the truth about her father, she asks, “But why would he do those things?” To which Lieberman, a Jewish man and Holocaust survivor, answers: “We were rats. Unworthy of life. . . . He will give our life meaning. . . . We will contribute to the noble pursuit of science. Because if the mind of lesser beings can be controlled, we can become productive. Useful. No need for wars and messy camps. We will help him make the world better” (118).

One of the most shocking elements of Cameron’s writing is to know the malleability of the mind and the techniques—both noble and ignoble—that can be used as psychological conditioning. Whether employing operant or classical conditioning, or even simple strategies of repetition—sometimes called brainwashing or mind training—our brains can be rewired and reprogrammed.

Another alarming aspect occurs when we wonder what it would have been like to be German in 1945 and be told that the ideal Nazi is tall, blond, and perfect. To be steeped in the ideology of a superior race to the point that it seems normal and right and that the noblest pursuit for a young girl is to reproduce and contribute to the supreme German race. This is Annemarie’s reality. When Russia liberates Germany, this lithe beauty is raped, beaten, and left for dead. Even though Inge rescues her, Annemarie’s mental state is precarious at best. Who she turns out to be and who she becomes add to the novel’s surprises.

Fueled by hate, guilt, shame, and repulsion, Inge’s goal takes her across the ocean to New York City, where she begins to hunt for her father. In America, under a new identity: Eva Gerst meets a group of immigrants at Powell House, including her sponsor: Jacob Katz. Jake is a clever young man with lovely eyes that notice everything and who moves to music inside his head. Training to be a writer of news, he has contacts everywhere. While trying to track down the Doctor, Eva and Jake realize that the United States and Russia are both seeking him as well—but for different reasons, motives, and purposes. Is he a good and brilliant man whose research can revolutionize the world, or a criminal who has committed unspeakable war crimes against humanity?

Even though she knows the pressure inside darkness and is often held in the jaws of fear, Eva gradually begins to find herself and learns to live with the holes left by loss and emptiness. As the truths unfold in this slow and grueling metamorphosis, the reader experiences both shock and surprise. Along with Eva, we realize that running will not allow us to escape what is inside our heads. We also come to accept that reality is the condition we create for ourselves and that none of us is capable of making the whole world a better place, just our small corner of it. Inspired by Cameron’s characters, readers derive encouragement to transform the world, one small act of kindness, fairness, and justice at a time. Armed with Eva’s courageous role modelling, a person can “upend their own beliefs and start again with something new” (Author’s Notes). After all, without critical thinking and without the asking of questions about many of the beliefs to which we are today subjected—“beliefs not so different from the Nazi ones” (421)–about who is better and which immigrants have value, we risk repeating the past.

Additional benefits of this book can be found in the Author’s Notes. Here, Cameron reveal valuable history about various CIA projects, including Project Bluebird, the one on which her novel is based; concentration camps like Sachsenhausen; Lebensborn and children stolen from Poland; and Powell House and the American Friends Service Committee.

- Posted by Donna