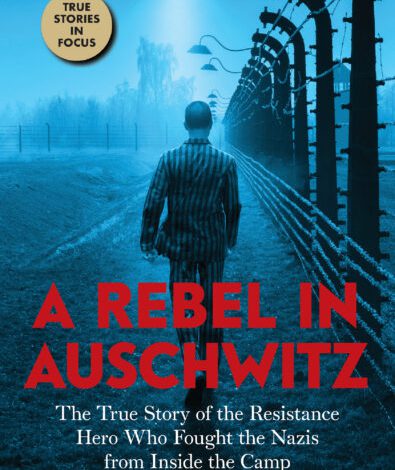

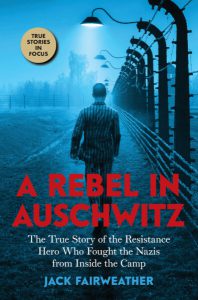

In his newest book, A Rebel in Auschwitz, Jack Fairweather tells the true story of a resistance hero who fought the Nazis from inside the tortuous prison camp. The book opens with an introduction to Witold Pilecki, a young Polish underground operative. Once readers have a sense of this man’s values, we read about Hitler’s goal to obliterate the Polish people as well as their nation—“to drown the people in blood” (12).

In his newest book, A Rebel in Auschwitz, Jack Fairweather tells the true story of a resistance hero who fought the Nazis from inside the tortuous prison camp. The book opens with an introduction to Witold Pilecki, a young Polish underground operative. Once readers have a sense of this man’s values, we read about Hitler’s goal to obliterate the Polish people as well as their nation—“to drown the people in blood” (12).

Feeling it is imperative to face down evil, Witold accepts a mission to infiltrate Auschwitz so that he can pass on any intelligence to the resistance group and rally the power of the Allies. Despite the dire challenges and dangers in Auschwitz—where the chimney of the crematory seems to be the only way to freedom—Witold and his group of recruits refuse to accept the camp’s subverted moral order. They brave brutality, starvation, lice, and disease in order to ensure a better life for others.

One of the most powerful messages of Fairweather’s harrowing account of this historical period is to document the heroism of many who fought against the carnal and vicious natures of some men. Fairweather poses the still important question: What do we gain when a social system pits ethnic groups against one another? For evidence of an answer, we need only to study history and Hitler’s efforts with his racial project to assert that Germans were the master race. In fact, we tear apart the social fabric of our nation in such pursuits.

It is shocking to read about some men who could simultaneously inhabit the brutal world inside the camp and that beyond its walls. To encounter such monsters makes one wonder whether Witold is the greatest hero or the biggest fool! Despite nearly three years of Witold’s grueling work to organize a resistance, the Allies did nothing to dismantle the death camps. “The Allies claimed they did not want to divert resources from the main task of defeating Hitler” (174-175).

Refusing to give up on his plan, Witold and his resistance cell needed to believe they had some control over their fate. “Despite now knowing that his reports would likely be met with indifference, Witold continued to gather intelligence on Nazi crimes. What else could he do? With spirits so fragile, he worried the underground would fracture entirely” (187).

In addition to the horror of the Holocaust, the reader will learn about the more than 90,000 Poles, who were actively involved in the rescue effort of Jewish families. Through these bold acts of resistance, Fairweather reminds us that most people don’t instinctively come to the rescue of others, especially when in danger and feeling threatened themselves. Through his character Witold, we are reminded that “no matter how gruesome the subject, no matter how difficult our own circumstances, we must never stop trying to understand the plight of others” (248).

- Posted by Donna