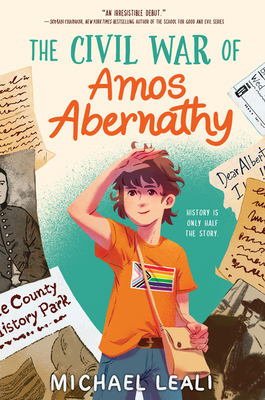

A historical reenactor in his own youth, author Michael Leali not only writes about his experiences in The Civil War of Amos Abernathy but invites all readers to challenge the histories we have been told. In this debut novel targeted for young readers, Leali focuses on thirteen-year-old Amos as he battles against entrenched attitudes and fights for his friends Ben Oglevie—a young man whose parents are homophobic—and Chloe Thompson—a young Black woman who wants to share the truth about her ancestors.

A historical reenactor in his own youth, author Michael Leali not only writes about his experiences in The Civil War of Amos Abernathy but invites all readers to challenge the histories we have been told. In this debut novel targeted for young readers, Leali focuses on thirteen-year-old Amos as he battles against entrenched attitudes and fights for his friends Ben Oglevie—a young man whose parents are homophobic—and Chloe Thompson—a young Black woman who wants to share the truth about her ancestors.

Reenacting 19th Century History is like time travel for Amos, who works as a junior volunteer at the Living History Park (LHP) in Apple Grove, Illinois. Here, he realizes that “if history isn’t comfortable, a lot of people don’t want to look at it” (14). Yet, much of history is awful and hurtful, and in order to ensure we don’t repeat the sins of the past, we often need to shine some light into those dark corners. Leali’s book does that. His protagonists ask the right questions and push the boundaries despite the discomfort that results for them and for those in positions of power. Although confronting the reality that some of our historical heroes were in fact villains might be difficult, sharing more of history expands our vision and enlarges the truth.

Hoping to find a connection to Chickaree County and to strengthen his sense of belonging, Amos wonders whether people were historically straight and cisgender or whether he has deeper roots. In his search for evidence, Amos discovers that he needs better questions and the right words. After all, the word homosexual wasn’t coined until 1869.

Discovering Albert D.J. Cashier is both life-changing and self-affirming for Amos. Even though the words didn’t exist during the Civil War era, Albert would likely have been a transgender man. This discovery gives Amos the inspiration to fight for queer pride, to tell the untold stories about erased or misrepresented identities, and to give voice to those silenced or forgotten. Although Amos believes that it’s harder for people to hate, ignore, or forget the marginalized when we all work together, he finds out just how progressive the semirural Midwest is and how much telling a story to a wider audience depends on who has power and money.

As they excavate the truth, Amos, Ben, and Chloe realize that just because they have never heard of something doesn’t make it impossible or untrue. For example, Black women were blacksmiths in the 1800s and Abraham Lincoln had bisexual tendencies.

While this novel has potential to enlarge the vision of all readers, it especially speaks to members of the queer community. It serves like a type of Trevor Project, only in book form. Amos not only practices ally behavior, he has allies all around him. One of those is Ms. Wiseman, his English teacher who says: “Language is constantly evolving. . . . It’s likely our understanding of sexuality and gender—identity as a whole—will shift again in the next ten, twenty, thirty years. The thing is, we don’t know what we don’t know. That makes looking back in history a challenge” (107). Not all young people are as fortunate to have this kind of support.

Amos also begins to wonder about reenacting and the possible wrongness of putting on a costume and pretending something like war is entertainment. After all, “war isn’t entertainment—this is supposed to be a time to honor, remember, [and] contend with one of the ugliest truths of America,” (174). Rather than responding with anger and frustration alone, Amos decides to push past his initial shock and disbelief to do something that might effect change.

Once he has seen this truth, Amos can’t unsee it. He and Chloe decide that “maybe if we want things to change, we have to stop waiting. Maybe we just need to do something about [telling the truth, changing the narrative, and sharing the stories of marginalized people] ourselves” (184). Determined to combat the destructive and alienating forces of hatred, the duo plans to flood the LHP with knowledge.

Not seeking to change history but hoping to share more of it, Chloe and Amos go to work. In their commitment to erasing ignorance, their need for knowledge gives rise to honest questioning. Under the influence of this duo’s epiphany, readers come to accept that knowledge flows to the point of greatest ignorance. We should not allow our current knowing or our attitudes about the status quo to function as a dam, preventing additional knowledge from flowing to us.

In this struggle, readers discover one of the biggest take-aways from Leali’s book: that whatever my business might be, I’m best served when I begin it by locating the place where I know the least. That process of unknowing often begins with curiosity and the asking of questions—some of which may appear ignorant to those who don’t realize we are trying to dismantle a dam.

The novel’s title hints at another key point—that we all share struggles, confusions, and frustrations that pull us in different directions, putting us at war with ourselves. These warring factions can cause us to lose our civility. “We’re supposed to be living in this progressive time, but people are still treated like garbage and discriminated against all the time. It’s like no matter how much we do, it’ll never be enough. There’s always more fighting to be done. Just one time, I don’t want to have to fight” (232).

Despite this level of despair, Amos finds room for possibility. He and his friends find ample stories of Black people, Indigenous people, LGBTQ+ people, and other marginalized groups in history. “For too long we’ve listened to one narrative, one perspective of history. But today, we ask you to challenge the histories you’ve been told. Look for answers to the questions you didn’t know you should be asking, Find the people who didn’t make it into your textbooks. They deserve to be known” (263).

Because of these missing records, important details have been left out of the human story. Like lying by omission, prejudices and biases can get in the way of truth-telling.

- Posted by Donna