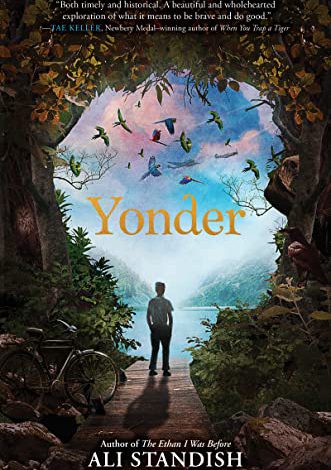

Readers of Katherine Patterson will likely appreciate Yonder by Ali Standish. The community of Foggy Gap proves the world is a confusing place—with gaps in understanding and with clarity of vision required on subjects like justice, prejudice, war, and courage.

Readers of Katherine Patterson will likely appreciate Yonder by Ali Standish. The community of Foggy Gap proves the world is a confusing place—with gaps in understanding and with clarity of vision required on subjects like justice, prejudice, war, and courage.

Set in the early 1940s, Standish shares a perspective of what the years surrounding World War II may have been like in the United States. Her story suggests that the country’s role in WWII is more complicated than many of us are taught to believe, especially in the way in which news about Hitler’s Jewish extermination campaign was publicized or received limited coverage.

For the most part, this is a book about the importance of having a conscience. Twelve-year-old Danny Timmons who collects baseball cards but endures bullying for his lack of perceived courage learns from his mother that being raised in a small town is no excuse for having a small mind.

From sixteen-year-old Jack Bailey, readers recognize that there are many ways of being smart. Although not book smart, Jack has an uncanny knowledge of the forest. He also introduces us to Yonder, a magical utopia like Terabithia, a view of something hopeful and heavenly. He is the victim of an abusive father suffering from PTSD incurred from his time in WWI.

A lover of Nancy Drew mysteries who wears her low deportment grades as a badge of honor, Lou Maguire wants to be a detective. Her family falls prey to small mindedness when her brother George enlists in the army but then defects.

As they read about this trio of young people, readers will gather along with them several morals. Some of these include how we draw inspiration for our actions from models: “Until people see [both the horrors and the heroism of war] there in front of them, it won’t be real to them. They need to read it from their papers, hear it from their radios. . . . If [people] don’t see an injustice, then they don’t have to take a stand” (215).

Believing that evil is only as powerful as we let it be, Danny’s mother, Dorothy—who works for the newspaper—takes criticism for her efforts to shine light on the extermination camps and the killing of Jews. With her transparent reporting, she wants people to understand that the war isn’t just about land, democracy, and sovereignty but about humanity. She tells her son: “Prejudice is like . . . like a germ, or a virus. Nobody is immune. That sickness—that evil—it can take many forms. In Germany, it created those camps. Here, it created segregation, and slavery before that” (216).

Another message comes from Daphne Musgrave, a Black woman whose family is forced from their home because of bigotry, “[Living in Pittsburgh] is not the life we meant to build, but if it is the one we are to lead, we will fill it with hope and love and joy” (292). With her attitude of positivity, she teaches us that although we may not choose our circumstances, we do choose our reaction to and attitude about them. After all, the world isn’t often a fair place, but we can all make things more right when we can see what’s wrong. Each of us has to do our part—a part that only our own heart can tell us.

Ultimately, Danny learns that just as making mistakes is a part of life, so is setting out to correct those wrongs. From him, we all recognize the value in confronting small injustices and come to understand that true courage is about standing up to evil in all of its forms—whether bullying, child abuse, prejudice, or something more monstrous. “I was starting to see how a little wrong made way for another little wrong, and another and another, until all those wrongs became something enormous and monstrous and wicked” (317).

- Posted by Donna