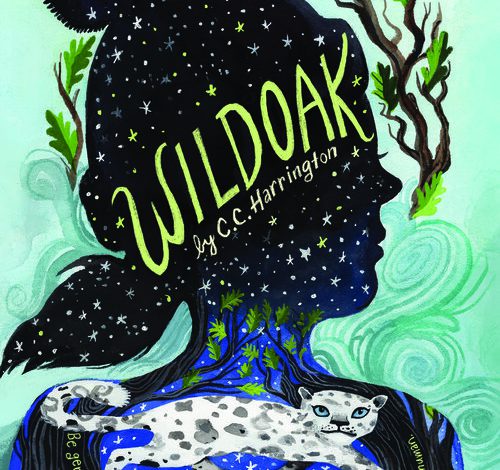

Set in London in 1963, Wildoak by C.C. Harrington features eleven-year-old Margaret Stephens. Maggie stutters, but not whenever she speaks to her pet mouse Wellington or to the injured dove Flute whose wing she has wrapped for healing or to the two snails, Spitfire and Hurricaine, whom she has rescued from the garden. Still, it’s not her gifts that she sees. Maggie sees herself as broken, a child that doesn’t work properly.

Some of these fears derive from people’s reactions to her blocking and her inability to get the words out. Her father even threatens to send her to Granville, a special school where rumor speaks of starvation, neglect, and corporal punishment. More than anything, Maggie wishes “to speak without stuttering, to say whatever she wanted to say. To be understood. To be heard” (8).

Out of love mixed with fear that Maggie is struggling and needs to find another way forward, Mrs. Stephens, Maggie’s mother, determines that a trip to the Cornwall countryside to stay with her father, Dr. Tremayne, will help Maggie. Although Maggie doesn’t really know Grandpa Fred, to Cornwall she gets shipped.

Maggie discovers that Grandpa Fred is a terrible driver and somewhat eccentric in his desire to collect bits of nature and to invent things like flying automobiles, but he loves her and welcomes her into Cherry Tree Cottage.

Here, she visits Wildoak, “one of the last remaining pieces of ancient woodland in the whole of England” (66). Fred tells her it’s a magical place, and Maggie begins to feel a glimmer of possibility. After all, unbelievable things happen sometimes.

In Wildoak, Maggie discovers large ancient trees for climbing, some for housing animals, and others for cradling her in her tiredness. Leaning against one of the massive oaks, she senses a healing vibe, a kind of energy. While worrying about her differences and her challenges with speech, Maggie feels a vibration, and words echo back to her: “Be gentle with yourself. It is hard to be human” (79). Maggie does indeed know that it’s hard to be understood, hard to love and be loved, but in Wildoak, she feels free and unencumbered. The tightness in her shoulders and chest softens.

One day while exploring, Maggie finds a snow leopard kitten caught in a trap. Determined, she rescues the cat and begins the long process of nursing him back to health, despite the fact that Grandpa Fred insists there are no snow leopards in Wildoak. Eventually, Maggie learns the cat’s name is Rumpus. When his paw shows signs of infection, Maggie—who understands that words are only one way to carry messages—realizes that the forest can help. Relying on instinct and intuition, as well as by using Grandpa Fred’s books on medicinal plants, Maggie makes poultices, tinctures, and tonics to treat Rumpus.

But, it’s not just Rumpus’ injury that threatens his life. When other locals glimpse the cat, they are convinced he is a monster. They see a killer of sheep and children, not the playful, loving animal that Maggie has nursed. Furthermore, Lord Foy, who owns the land where the forest grows, has decided to clear it for a housing development. Wildoak would be no more.

All of these forces come together in Harrington’s book, and readers will have to discover their conclusion. In the process, they will encounter some key lessons, namely that “we do what we can, in our own small ways, and sometimes that’s enough to make a difference” (187). Harrington also adds a message about the value of diversity. Although all of us have something about ourselves that we wish to change—“whether it’s the way [we] look, the way [we] sound, where [we’re] from, what [we] own or what [we] don’t, . . .there’s room in this beautiful, complicated world of ours for all of us. Just as we are. In fact, there is a need for it” (293).

Maggie’s sense of shame morphs into something fierce and determined. She discovers that her stutter doesn’t have to stop her, that she can say what she needs to, that she can speak for the trees and the animals—it just might take her a little longer.

In addition to these messages and her allusions to Jane Goodall, Harrington includes an author’s note in which she not only shares resources for young people who experience stuttering but reports on reforestation efforts and wild cat conservation.

- Posted by Donna