In her novel The Whispering Dark, Kelly Andrew explores the question, to what extremes does love drive us? To tell her tale, Andrew creates seventeen-year-old Delaney Meyer-Petrov as her female lead and twenty-one year old Colton Price as her male lead. In this telling, there is also a villain: the Apostle.

As a young girl, Delaney endured a near-death episode that left her hearing impaired and rendered her parents overly attentive. With her hearing gone, Delaney personifies the darkness and imagines it alive and restless. Lane whispers her secrets to the shadows. Wishing to be defined by the sum of her achievements and her abilities rather than “by the silence between her ears or her fear of the dark” (5), Lane applies for a needs-based college scholarship and is accepted to Howe University’s Godbole School of Neo-Anthropological Studies.

Wanting to see if another version of her exists, Lane eagerly welcomes the bricks and books and new beginnings that Godbole represents. Here, she meets Colton Price, and their encounters are complicated and laced with contradiction. Because the students at Godbole are studying a brand of anthropology that borders on the occult, their interactions might pose foreign and somewhat unbelievable to some readers. However, by suspending disbelief, the reader will discover some very real human questions and conflicts surrounding death.

On this journey, readers learn some Latin phrases like non omnis moriar: “I shall not wholly die” (72), and we wonder about death, the pain of loss, and whether death can be rejected like a transplanted organ. Along with her characters, Andrew invites her readers to ask: What if, when we die, we leave a vacancy for something else to take up residence in our bodies? The Apostle has a theory that “if something immortal can be harnessed and packed into the body of someone mortal, he can prevent the human body from every suffering death” (308). As the theory goes, when we die, we leave behind an empty body into which something else can crawl, using it as a vessel. In essence, such a possibility hints at the prospect of immortality.

As Andrew spins her tapestry about whether walking in parallel universes, necromancy, or immortality are possible, the reader will encounter tangles as well as the occasional malus navis—a beacon of clarity. For example, we realize that we all do things that seem impractical—such as leaving gifts at gravesites—because these actions make us hurt a little less. Some of us may be so terrified by the prospect of loss, that we will go to extraordinary lengths to preserve the lives of those we love and can’t bear to lose.

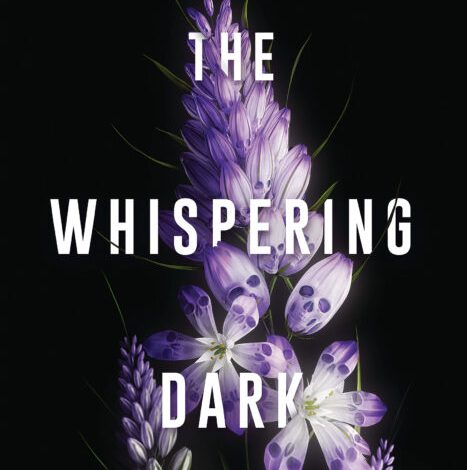

Andrew also explores the nature of purgatory, using the asphodel, a lily-like flower with spiritual meaning that dates back to Greek mythology. To the Greeks, the flower was a potent symbol of death, the afterlife, and the hope for eternal peace.

- Posted by Donna