Aneesa Marufu writes her debut dark fantasy, Rebel of Fire and Flight to explore the concepts of racism, classism, and gender roles. To tell her tale about freedom from oppression and the deep roots of hatred, Marufu creates the parallel stories of two teens: Khadija and Jacob. Set in the fictional South Asian country of Ghadaea and alternating between Khadija’s and Jacob’s experiences, the book allows readers to witness the lives of the pair and their individual challenges as they explore who they are and what they truly want in this world.

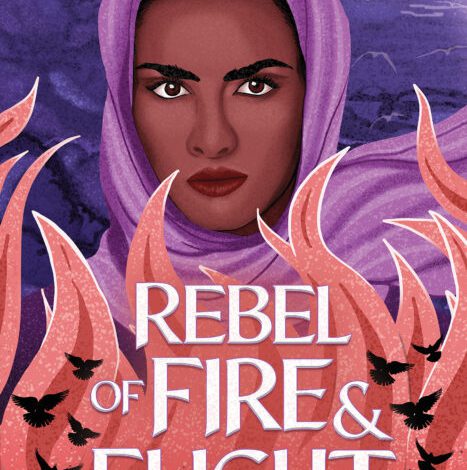

Sixteen-year-old Khadija is a brown-skinned Ghadean girl, who has spent a good deal of time secluded in her bedroom where she reads forbidden fantasy stories about princesses kidnapped by jinn, armies of female warriors, and hot air balloon escapes. She also draws, studying balloons in the way that some might study birds or wildflowers. In a social setting where girls are meant to be married and to care for a husband, children, and a home, Khadija sees balloons as untamed creatures, living, breathing, flying pieces of art. When her father introduces her to yet another unlikely match, Khadija flees her home in a stolen hot air balloon to escape life in an arranged marriage—a situation she perceives as akin to being under house arrest where she is forced to hide what she knows.

When she lands in the village of Sahli, Khadija finds an unlikely ally in a glassmaker’s apprentice, Jacob. A fair-skinned hāri boy, Jacob is similarly searching to escape poverty and trying to make life less hopeless. Drawn to the Hariff, rebels led by Vera, Jacob wonders whether the life promised—“You want to see our people happy, without fear, living the way we want” (74)—is possible with these freedom fighters. Although they use brute force more than other methods, the rebels seem to value intelligence and talent. With her words, Vera weaves a world where there is no fear, no hate, and no violence.

Khadija is similarly drawn to a rebel group, the Wāzeem, who also seek justice. But their tactics focus more on protests than on violence. Anam, a transgender female, leads the Wāzeem, who want equality, fairness, and “a better world for both races” (125).

Although both teens wish to rid the world of greed and hatred, they learn that inflicting harm without good reason means something different for everyone and that a single moment can change everything.

Marufu’s book encourages all readers to consider the insidious effects of hatred, racism, and prejudice—forces that seek to oppress, to hurt, to invalidate, or even to kill. Readers, along with Marufu’s characters, further realize that the world is not so black-and-white, good and bad, or us and them. Eradicating one race or one class of people to preserve the lives of the other is not the solution.

One of the moments of greatest clarity in the book comes during a description of skin: “In the dark, it was just skin. It was not an outfit or a piece of armor. It was not something to be worn or something to hide behind. It was not a freedom flag flying in the wind or a ticket to a better life. It was not a guarantee of oppression or a promise of privilege. It was human skin” (257).

Another moment of great insight occurs in Marufu’s observation that humans have the tendency to view a group of people based on the behaviors of a minority who tarnish the reputation of all: “It wasn’t fair how an entire race of people could be judged by the extremist actions of a small minority” (228).

- Posted by Donna