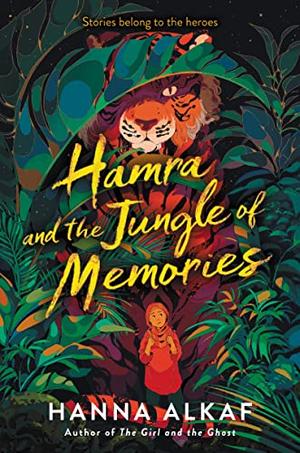

In writing Hamra and the Jungle of Memories, Hanna Alkaf begins in the fashion of a traditional fairy tale. In her reimagining of Little Red Riding Hood, Alkaf borrows heavily from the Malaysian Muslim culture and weaves her magical retelling with Malay customs and cuisine.

The star of this tale is thirteen-year-old Hamra, who is stubborn, sad, rebellious, and angry. She is tired of wiping up messes and cooking and listening to her grandmother say things that don’t’ make sense now that she is living with dementia. Hamra is tired of always having to be nice and good and polite and responsible. And she is tired of following unexplained and nonsensical rules. However, when she deliberately violates several rules of the Malaysian Jungle, she is unprepared to face the consequences.

Hamra’s best friend is Ilyas Chang Abdullah, a bird-lover who is prepared for anything and has a habit of swooping in to save the day—even when Hamra feels like she doesn’t need rescuing.

Realizing that a thief does not get to dictate the consequences of her actions, Hamra is now bound to the weretiger of Langkawi for stealing a jamba fruit from a jungle tree. Together with Ilyas, the trio must fulfill a quest to recover the weretiger’s true name, a discovery that will enable him to return to his human form.

In addition to their adventures, Alkaf shares a variety of key insights about human nature. For instance, Hamra learns that it is wise to exercise skepticism: “As wondrous as [the market’s wares appear], much of the market is built on the buying and selling of glamour and illusion, on slippery words and trickery. You must look for what is true and hold fast to it” (112), the weretiger tells Harma.

Hamra also realizes that things become clear in the doing and that with every piece of herself that she gives up for a moment’s pleasure is a piece that she loses forever. Despite her desire to rationalize that she really had no other choice, Hamra must admit that choices aren’t as limited as she believes. “There are only so many pieces you can give away before you lose yourself altogether” (126), the tiger reveals. And based on his past, the tiger is well aware that power is useless if in the end, those choices compromise one’s core identity.

As her grandmother Opah’s memory disappears, Hamra begins to wonder at the value of memory. “The thing about memories,” the tiger declares, “is that you never know which of them are important until you really truly need them” (233).

Another discovery that Hamra makes is that a prayer is comparable to a wish: “But prayer alone is not enough,” the praying man tells Hamra. “Desires are fulfilled only when efforts are made” (253).

From Hamra, we further understand that being human is difficult. “There’re a lot of messy uncomfortable feelings involved, like anger and sadness and hurt and guilt. But there are also so many beautiful moments, and there’s friendship, and there’s love. . . . And sometimes you like the results and sometimes you don’t. But there’s a lot of magic and wonder in the trying” (315). Ultimately, we come to accept that the strongest magic derives from the powers of courage and conviction.

- Posted by Donna