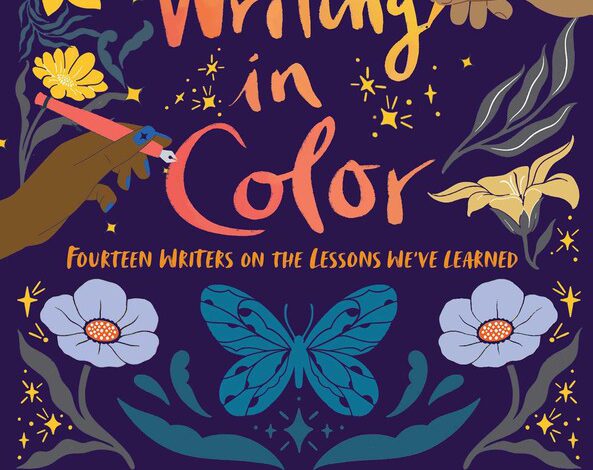

Edited by Nafiza Azad and Melody Simpson, Writing in Color is a guidebook of sorts for any aspiring writer. This collection of fourteen essays not only shares lessons on the writing craft and the publishing trade but offers encouragement and advice to all of us.

One tidbit of wisdom suggests that to grow as writers, we need to explore the world. The more experiences we acquire and the more perspectives we are able to take, the more material we will have at our disposal for storytelling and empowerment purposes. After all, “stories are vessels of entertainment, understanding, and knowledge; they change every person they touch” (230).

Another suggests that an individual’s worldview is influenced by culture. Joan He explains that although some people want autonomy, emotional independence, and the right to privacy, others prioritize “in-group harmony over personal preferences and see emotional dependence as a strength rather than a flaw” (67). Gail Villanueva adds: “Love your skin. Write your truths. Be unapologetically you” (184).

This book is comprised entirely of essays written by non-white writers, so occasionally, it calls out white supremacy and comments on the colorist and elitist publishing industry that causes these writers to feel marginalized. Cindy Pon writes: “When it comes to stories, so many editors aim to see their own narratives in what they acquire. Whatever the exciting difference or edginess is, it can’t be that different. It can’t push them outside of their comfort zones. And this is exactly what we, as marginalized writers, often bring to the table—stories that might not seem familiar enough, stories that challenge the status quo, stories that don’t feel as ‘relatable’” (151). Yet, such stories have the power to enrich us all.

These authors also remind writers that no story is perfect, but “as long as [writers] approach [their] writing with respect and thought and research” (160), they can typically outrun self-rejection, fear, and insecurity.

Other lessons reach beyond the audience of writers. For example, knowing that we silence doubt by raising our voices encourages us to speak out on topics that matter, on subjects, policies, or practices that we would like to see changed. We can further acknowledge how fear, doubt, and criticism can skew our views or how competition can become toxic within a community that should be helping one another to dismantle oppressive ideals.

My favorite essay was “Coping with Imposter Syndrome” by Julian Winters. “There is no limit to where doubt can seed itself and grow,” he writes. We need to set goals that are realistic and to remember that “while some of these things are achievable, most aren’t fully controlled by [us]. There are external factors that come into play. [We] can’t control trends, [for example, or] what people like or value as worthy” (191-192).

With its message of affirmation, this book has potential to provide inspiration to all readers.

- Posted by Donna