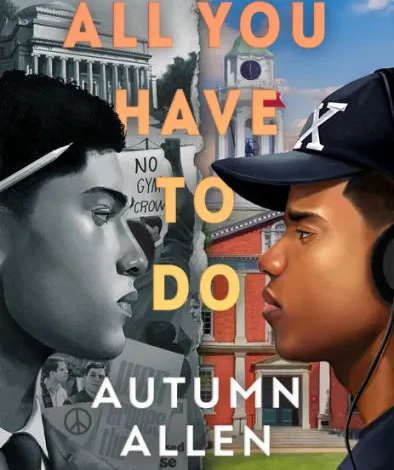

All You Have to Do by Autumn Allen invites readers to consider some important issues and to answer some key questions. Allen follows the lives of two black men: Kevin, an activist in 1968, and his nephew Gibran Wilson, a high school senior in 1995 attending Lakeside Academy in New York.

Allen’s intergenerational story is about “Black people taking care of business—the business of and for Black people” (37). It shares the similarities in the fights both young men have in exercising control over their lives, politically, economically, and psychically.

Through her two protagonists, Allen asks: Do we join the world with all its imperfections or do we actively seek to change it? Although violence is the only language some people understand, its collateral damage sends messages the sender often wishes to avoid. However, because change isn’t happening fast enough for either young man, each considers the option of self-sabotage, which feels better than doing nothing.

For Gibran’s mother, Dawn, clinging to hope and faith are alternate avenues. She is proof that faith can protect us so that rage doesn’t destroy us.

In addition to this magical mom, Gibran’s grandfather speaks wise words upon the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Junior: “In times of shock and grief, people do unusual things. They lash out. They take risks. They behave in ways they normally wouldn’t. We have to be smarter than that, son” (113).

Even though sometimes we have to take risks to get anything to change, Grandfather’s words remind us that acting on anger doesn’t end well. Although anger fuels action, we should only proceed once our rational mind has regained control. Eventually, Kevin realizes that “agitation [might] get things going, but it’s patience that keeps things moving. And strategy. Strategy keeps a steady flame alive. And strategy requires some level of unity” (388).

Still, Gibran finds a certain power in becoming outlandish and unpredictable, something with a threat of danger close beneath the surface. Having to choose between this power and the cowering he is used to proves to be no contest. Will this shift in focus prevent him from graduating and securing a scholarship to Howard University? If so, will the sacrifice be worth the fight? Like his uncle, Gibran believes he’d “rather die on [his] feet than live on [his] knees” (273).

Ultimately, Allen shares how Gibran has to learn that it’s not yelling the loudest that gets a person heard; it’s patiently staying the course, making baby steps and in-roads. “. . . The work can’t start and end with one man. We each do what we can with what we have from where we are. That’s how we keep moving in the right direction” (297-298).

Essentially, the book’s moral reveals that all of us have to make do with what the world gives us while also trying to make the world a better place. After all, compromise doesn’t mean giving up or losing. “Our work, each of us, we’re only adding pieces to the puzzle. You may not see all the change you’re working for, [but] that doesn’t mean you did nothing. It still matters” (299).

With plenty of allusions to activists, Allen joins other inspirational Black voices, like that of Angie Thomas, to make her case in writing this historical fiction account.

- Posted by Donna